This exclusive Cogs of War interview is with Bret C. Devereaux, an ancient military historian and Teaching Assistant Professor in the Department of World Languages and Cultures at North Carolina State University. As one of the earliest detailed records of how technology drives war and statecraft, Thucydides’ history proves a valuable guide to the human element for strategists and practitioners amid a time of great technical change.

Thucydides is often described as a founder of the discipline of history, a writer who sought to explain events through causes rather than divine will or myth. In his effort to establish this new kind of inquiry, what role does technology play in his understanding of how history should be related? Does he treat technological change as part of the causal structure of events, or as background to the political and moral drama he describes?

I think we have to begin by noting that among scholars, some of the root assumptions behind this question are actually contested. The way this period is generally taught and understood broadly through military history is that the Peloponnesian War represents, and thus Thucydides is documenting, the last years of a long-established and relatively static Greek military system which had emerged centuries earlier in the 700s and 600s BCE and remained largely static from the late 600s BCE to the start of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BCE. That older system, it is supposed, was based around decisive battles involving clashes of armies consisting almost entirely of heavy infantry hoplites, with minimal focus on sieges or raids and relatively little use of terrain, technology, or stratagems. In this vision, this system of more limited war crumbles under the pressure of the Peloponnesian War, such that we see the first hints of more sophisticated — or more ruthless — ways of war in Thucydides that will bloom more clearly in the works of Xenophon and eventually culminate in the more complex warfare of the fourth century, complete with catapults, massive warships and combined-arms armies.

However, that understanding of Thucydides has come under increasing pressure as a consequence of the long debates of the development and nature of hoplites, the standard Greek form of heavy infantry, and the phalanx in which they fought. Hoplite ‘heterodox’ (or even ‘heretic’) scholars, like Peter Krentz, Hans van Wees, Fernando Echeverría and Roel Konijnendijk, to name just a handful, argue that the hoplite-centric form of warfare that Thucydides treats as normal did not fully emerge in the 600s BCE, but emerged out of a process of evolution beginning in the eighth century and running all the way to the Persian Wars (492 to 490 BCE, 480 to 479 BCE). If that view is accepted, many of the tactical innovations in Thucydides are not new inventions but rather elements of Greek warfare that never fully went away, while the ‘old style’ of hoplite warfare that Thucydides treats as long-established was itself a relatively new and apparently unstable tactical paradigm that may have only fully emerged in the first decades of the 400s BCE and would begin to crumble within Thucydides’ lifetime (c. 460 to c. 400 BCE). These scholars would certainly still, I suspect, agree that Thucydides is documenting a period of significant change, but with the caveat that this is not a sudden revolutionary shift in warfare but rather an acceleration of changes, particularly in tactics and equipment, that have been going on for some time. That said, in either case, Thucydides is at most documenting just the first shoots of these changes — the full bloom will not come until the decades after his death.

The Peloponnesian War unfolded during a period of technical, tactical experimentation, but also human change. Does Thucydides appear to grasp that he is documenting such a moment?

For his part, Thucydides certainly seems to think that he has lived through a war that was shocking in both its scope and its conduct, a period of remarkable military change, not in weapons or technology, but in the scale of warfare and its increasing lack of restrictions. Thucydides opens by describing the war as “the greatest shift for the Greeks and some part of the barbarians” and repeatedly expresses shock at great military catastrophes, for instance, at the surrender of tactically outmaneuvered Spartans at Pylos or the crushing loss of the Athenian expedition to Sicily.

That said, I think it is important to clearly separate here the distinction between changes in the technology of war and changes in the human element. Thucydides’ account of the war opens with a deep history, commonly known as the Archaeology, in which the emergence of new technologies, such as the first navies or walled cities, play a crucial part. However, by Thucydides’ day these were all quite old technologies, and Thucydides’ understanding of their emergence is as much legendary as historical. Thucydides himself supposes the first Greek triremes to have been built shortly before the Persian Wars (492 to 479 BCE), so this technology was already at least sixty years old when the Peloponnesian War started. Thucydides offers no hint that he is even able to detect the emergence of the land warfare paradigm, hoplite warfare, that dominates his writing.

Indeed, when it comes to weapons and machines, Thucydides records relatively few technological changes. There is the use of a large bellows to set fire to the Athenian fort at Delium, a one-off not widely repeated. Likewise the Syracusan innovation of reinforcing the bows of their warships is an innovation Thucydides mentions but which nevertheless plays no apparent role in the subsequent decisive Syracusan naval victory in the Great Harbor, though we generally suppose this to be the starting point of a path of military innovation towards larger and heavier warships which will only bear fruit after Thucydides’ death. Instead, by and large, the material of warfare, ships and arms, and armor, remained largely unchanged and indeed had remained largely unchanged for most of the fifth century. One can sense in Thucydides the political pressures that will produce the heady and rapid military change of the fourth century, but that change itself is not yet evident.

By contrast, it is the change in the human element and the bounds of warfare that humans devise: the frequency of sieges, increasing tactical complexity, the use of naval raiding, the size of armies, the scale of funds spent and the spiral of escalating violence leading to the destruction of whole cities where one senses that Thucydides sees his world changing beneath his feet.

Thucydides’ descriptions of sieges and fortifications are unusually detailed for the era. What do these passages reveal about his technical literacy and the advancement of Greek engineering and siege tactics?

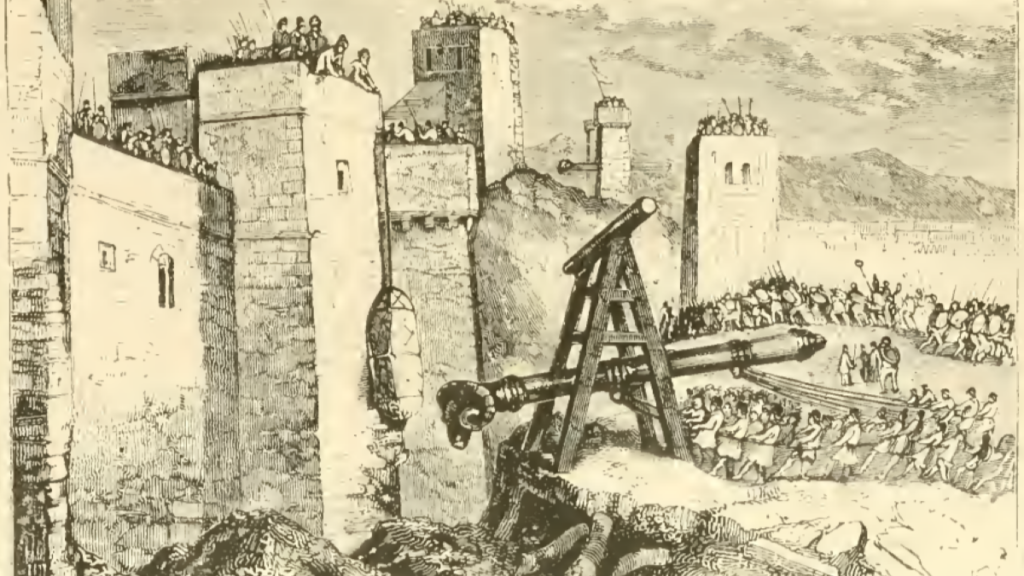

We need to be clear from the outset that Greece in Thucydides’ day was, compared to the Near East, remarkably backward in siege technology. Thucydides’ sieges consist almost entirely of attackers constructing walls around enemy cities to isolate them (circumvallation) and defenders constructing counter-walls to prevent this. Notably, efforts at greater sophistication than this generally fail. The Assyrians, dominating the Near East, by contrast, were using covered rams, siege towers, and complex field engineering, technologies entirely unknown to Thucydides’ Greeks, at least two and a half centuries before the Peloponnesian War. And Greek siege technology, as noted, changes very little across Thucydides’ work.

What is changing, however, is the human element: the political and strategic context of these sieges. As best we can tell, true sieges in Greece prior to the Peloponnesian War were relatively rare, as few Greek poleis had the resources or desire to mount such prolonged operations. Polis armies, essentially weekend-warrior citizen militias, could not be kept in the field that long. And we see that play out at the beginning of the war, with the failed Spartan effort to take even an outlying fortified Athenian settlement at Oenoe. However, as the war escalates both in scale and violence, we see Greek states increasingly willing to commit the resources and time for long sieges aiming at absolute victory, as with the Theban siege of Plataea or the Athenian siege of Syracuse, both of which lasted more than two years, the former successful, the latter a failure. While the resources the Greeks will devote to siege warfare clearly increase over the course of the war, the innovations that will allow Greek sieges to be more regularly effective will come only in the fourth century.

The History occasionally treats ships, armor, and siegecraft almost as characters in their own right, such as the walls at Syracuse, the Athenian trireme, and Plataea’s siegeworks. To what extent do you see these moments as less about technology itself and more about the human emotions, morale, and will that those objects come to embody?

Following on from the last point, the relatively rare points where Thucydides seems to dwell on the materiel of war, it often seems to represent the human emotions behind those objects. The long blockade of Plataea, in its moves and counter-moves, reflects less the dominance of technology (indeed, the innovative efforts to take the city all fail, leading to a traditional blockade), but more the human element in stubbornness of the defenders, the audacity of their successful breakout and the eventual failure of the defense from starvation and exhaustion rather than breakthrough. Likewise, the competing defensive works and fleet construction in the siege of Syracuse in many ways reflect the competing determination of the expedition and the Syracusans, waxing and waning as the confidence of the two sides does. Strikingly, Thucydides notes that the Athenians, even after their defeat in the Great Harbor, have enough ships to make another attempt at a naval battle, potentially even with superiority of numbers, but their demoralized sailors refuse to make the attempt. What was decisive was not the material, but the men — the will of the Athenian crews broke long before the timbers of their ships did.

Thucydides never names a “defense industrial base,” yet his Athens hums like one with miners at Laurion, shipwrights at the Piraeus, and tribute flowing through the empire. Do you think he would have agreed that war had become an industry?

We might more accurately say that Thucydides thinks of war more like a business than like an industry. War is financial in nature for Thucydides, the fundamental resource being money, with which any other necessary resource may be easily purchased. For example, given the tremendous naval activity during the war and the remarkably short service lives of ancient warships, the demand for timber and shipbuilding must have been considerable, but Thucydides rarely mentions lumber or construction crews for ships. When he does mention ship construction, the timber and labor simply materialize as a consequence of the expenditure of money. The Syracusans, under siege and pressured by the Athenians, set out to build a fleet and it simply happens, without much discussion of how the ships were readied. Likewise, the Athenians, forced to rebuild their fleet from scratch, simply “contributed timber and got on with their shipbuilding.”

Thucydides is likewise generally unconcerned about how the production of weapons will be accomplished. What he is quite concerned with, in contrast, was the cost to the treasury of this activity. Thucydides pays careful attention to Athens’ revenues and stockpiles of money (in the form of silver bullion) in contrast to the Peloponnesian lack of such monetary resources. Thucydides likewise carefully accounts for the financial cost to the treasury of the Athenian fleet or Athenian troop deployments.

If war consumes money in Thucydides, the other side of this same coin is the repeated expectation, particularly by the Athenians, that war might lead to profit. As Thucydides makes clear, Athens’ power and prosperity at the start of the war rested primarily on the vast amount of tribute it extracted from subjugated Greek cities. Where raw resources do come up in Thucydides, it is in the context of potential gains to be had from conquest, though the potential spoils of future victories are still generally expressed in money. Athens’ tributary empire thus operated like a warfare business: Athens’ fleet enabled the subjugation of other Greek poleis whose financial contributions in turn funded the fleet and Athens’ own public works and programs. But as to the industrial details beyond that financial relationship, Thucydides pays little mind.

How does Thucydides’ treatment of technology compare with Herodotus or later historians like Polybius?

The contrast between Thucydides and Polybius in this regard is particularly striking. Thucydides chronicles a war in which both sides fought the war from beginning to end with armies made up principally of hoplites and navies made up of triremes, the largest shift being somewhat broader employment of other combat arms, cavalry, and light infantry. Although, as Roel Konijnendijk has documented in particular, these were hardly new additions to the Greek battlefield. In short, the armies and navies Thucydides describes are largely technologically stable and symmetrical, and so he feels little need to discuss the specific designs of ships or weapons or the production thereof.

By contrast, Polybius’ history covers a period of substantial change, with wars between forces that were asymmetrical in their materiel. Consequently, Polybius is very interested in the performance of specific kinds of weapons and makes a point of documenting the Roman adoption of foreign technologies, such as the Roman imitation of Carthaginian ships. Though the historicity of the Romans needing to copy Carthaginian ships has been questioned, as the Romans were not quite such novices as Polybius implies. Polybius is also documenting, it must be noted, armies that are a great deal more technically sophisticated than those of Thucydides’ day: Complex siege operations, catapults, larger warships, and frequent integrated combined arms warfare, all rare or unknown for Thucydides, were ubiquitous in the warfare of Polybius’ day.

***

Bret C. Devereaux is a teaching assistant professor at North Carolina State University and a historian whose research focuses on the intersection of the economy and military of the Roman Republic. He also writes a weekly history blog, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry (acoup.blog), and has an upcoming book, Of Arms and Men: Why Rome Always Won, a comparative study of mobilization and the costs of fielding armies in the Mediterranean during the third and second centuries BCE.

Image: Elbert Perce via Wikimedia Commons.