For most Catholics, Dec. 8 is known as the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception. In Albania, the same date carries an additional meaning. It marks the student protests of Dec. 8, 1990 — later commemorated as National Youth Day — the first public rupture in the last, most rigid communist regime in Europe.

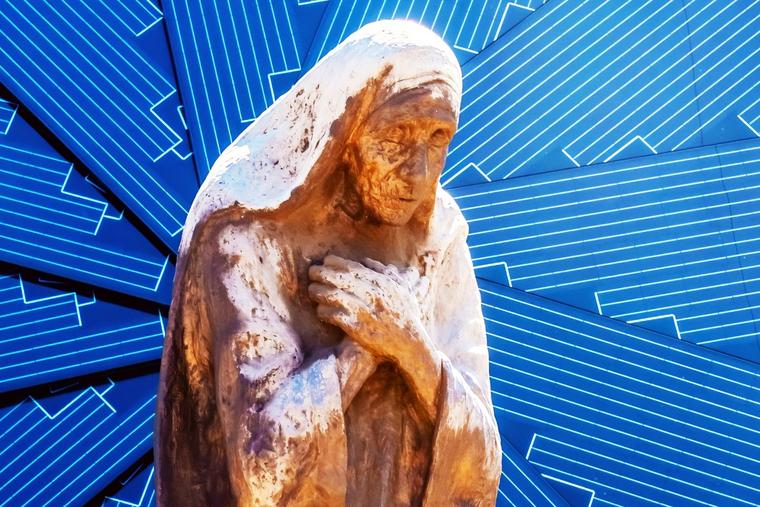

Mother Teresa at the Edge of the Regime’s Collapse

The week before that historic day, St. Teresa of Calcutta returned to Albania while the communist system was visibly failing. In internal communications, party officials recorded that she met Nexhmije Hoxha (widow of the Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha) on Dec. 3 and President Ramiz Alia (who succeeded Enver Hoxha after the dictator’s death) on Dec. 4. Mother Teresa’s aim was direct: she wanted to bring the Missionaries of Charity to Albania.

The regime’s response was telling — and entirely in keeping with what one would expect from seasoned communist leaders. Nexhmije Hoxha did not offer a clear refusal. Instead, she promised that Mother Teresa’s request would be “reviewed” later by the “competent authorities,” adding that any concession would be made “to fulfill her wish as an Albanian,” not because the state “needed” the Missionaries of Charity’s assistance. The official ideology insisted that the socialist system already cared for the sick and elderly and required no help from outside — socialist self-sufficiency at its best.

But that phrasing reveals a government running on fumes. The leadership could no longer rely on Marxist-Leninist ideological certainty to justify its control over conscience and freedom; it reached instead for patriotic language, treating Mother Teresa less as a religious sister and more as an Albanian national symbol.

Yet the very need to stall — rather than forbid — showed how quickly the regime’s ideology was collapsing. Within months, history outran the iron bureaucracy: the Missionaries of Charity began their work in Albania in March 1991, turning that vague “we will review it” into a public reversal by a state that had once outlawed religion and declared itself the world’s first atheistic state.

A Televised Crack in the Atheist ‘Eschatology’

Mother Teresa’s meeting with Ramiz Alia carried deeper theological weight. Alia addressed her not merely as “Mother Teresa of Calcutta,” but as “Mother Teresa of Albania,” praising her heart and her service to the suffering, and naming her a daughter of the Albanian people. Mother Teresa responded with disarming clarity: she had no gold, no silver — only the desire to bring her sisters to serve.

This exchange mattered because it forced the regime into a moral dilemma it could no longer manage. In a system built on the claim that religion was a social poison and that the state alone could provide meaning and care, Mother Teresa asked only for permission to love those the system failed to love.

This is why the moment functioned as more than diplomacy. Albania’s communism depended on an ideological eschatology — a promise of total transformation through the eradication of religion, a paradise constructed by force of doctrine alone. When the leader of that system publicly praised a Catholic nun for her sanctity and generosity, the regime’s narrative fractured on live television. For ordinary citizens, the message was unmistakable: Faith was no longer automatically treason.

In biblical terms, the scene resembles a solitary witness confronting power not with violence, but with the authority of charity — like Elijah before Ahab, or the Gospel’s insistence that the last can become first.

Youth, Candles and a New Voice

Only three days after Mother Teresa left Albania, the moral crack became political. On Dec. 8, 1990, students marched from the Tirana University dormitories into the streets of the capital. What began with roughly 300 students grew rapidly; within days, the crowds reached into the thousands, and pressure mounted on the government to accept political pluralism.

The protest developed into a strike involving the university community — students and professors — articulating demands for democratic reforms. On Dec. 11, Ramiz Alia met with student representatives and agreed to address grievances that only weeks earlier would have been unthinkable.

Albania later chose to remember that first public step. Since 2009, the country has commemorated Dec. 8 as National Youth Day, honoring the students whose protest ignited the transition and became intertwined with other symbolic moments, including the toppling of Enver Hoxha’s statue in early 1991.

Even without a confessional frame, the civic meaning is clear: Albania’s passage out of totalitarian control began when young people — long trained in silence and ideology — lit the first public candle of dissent.

Constellations of Dates

If the tools of a Catholic theological imagination are in place, one can connect the dots and notice how often modern anti-communist turning points cluster around Marian devotion. The Fátima apparitions (1917) are frequently read as prophetic of the 20th century’s spiritual conflict, with their call to conversion, prayer and devotion to the Immaculate Heart. In this devotional interpretation, the “errors” of militant atheism are not simply political mistakes but spiritual distortions that attempt to erase God from the human heart.

Later, Pope St. John Paul II — who had personally lived under communist dictatorship in his native Poland — intentionally dated key Marian gestures to speak into that conflict: a letter to bishops on Dec. 8, 1983, urging a consecration of the world to the Immaculate Heart, followed by the renewed act of consecration on March 25, 1984.

Then comes another Dec. 8. On Dec. 8, 1991, the USSR was formally dissolved through the Belovezha accords. Some Catholic journalists and commentators treated this as providential — perhaps coincidence, perhaps sign. Theology does not require proof of a mechanistic causal link between feast days and geopolitical outcomes, but it does permit a broader claim: History is not closed to meaning, and the Church is allowed to interpret events within an eschatological horizon, reading time in the light of Christ’s final victory.

A Revolution of Heart and Hope

The closing theological claim can be stated simply. Catholic tradition sees social transformation beginning not in slogans but in the human person: conscience, then heart, then hope. Vatican II describes conscience as the place where the human being encounters moral truth and is bound to obey it (Gaudium et Spes 16). When conscience awakens, it presses into the heart — the interior where love becomes concrete action: “love in deed and truth” (1 John 3:18). Hope then anchors both, as the divine gift that prevents moral awakening from collapsing into cynicism (Romans 5:5).

In this light, Mother Teresa’s visit to Albania just before the fall of socialism emerges as a catalyst. Her insistence on mercy confronted Albania’s atheist system with a choice between ideology and compassion, and her televised presence signaled that faith could re-enter public space. Meanwhile, the students’ protests that followed supplied the collective political break. The causes of communism’s fall in Albania were complex — economic collapse, social pressure, international changes — but the initial fracture was moral before it was structural.

That is why this moment holds such enduring power for Albanians, whether Christian or not. As the Church honored Mary’s conception without sin — the sign that grace can preserve and heal human freedom — Albanian youth stepped into the streets and insisted that their country could no longer be built on fear. In a providential reading, the Immaculate Heart of Mary stands beside the students’ candles as a shared icon of liberation — not liberation from history, but liberation within history, where conscience awakens, truth is spoken, and hope becomes possible again.

Seen this way, the convergence of Marian devotion and Mother Teresa’s mercy gives Albania a language to name its passage from fear to freedom as its own revolution of conscience.