Iran today stands at one of its most consequential junctures – or perhaps ruptures – since the so-called 1979 Revolution.

The state appears strong on the surface, yet underneath lies a system strained by economic decay, social alienation, elite rivalry, and the looming departure of its central arbiter: Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

A November 2025 interview, titled “What Kind of Future for Iran?, with Karim Sadjadpour*, conducted by Michael Young for Diwan, a blog from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Middle East Program and the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center, offers a valuable insight for understanding Iran’s current geopolitical moment-not as a story of inevitable democratisation, but as a high-risk transition shaped by coercion, ideology, and regional power struggles.

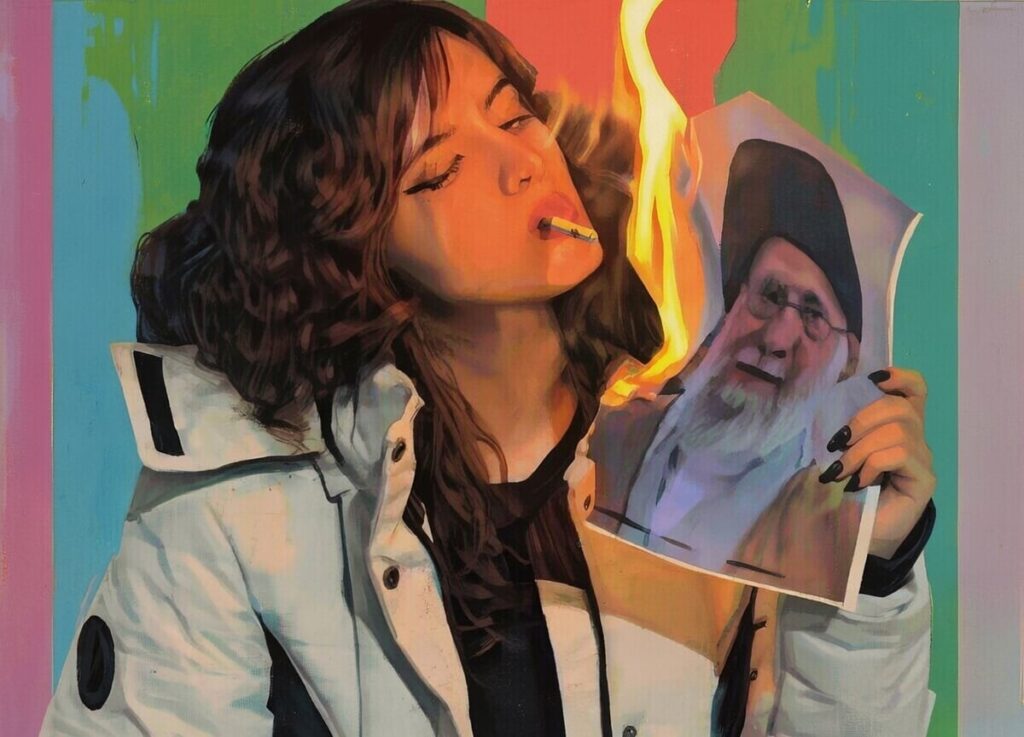

As images of the horrors of Tehran’s brutal repression against the anti-regime protestors filter out to the rest of the world, the many post-Islamic regime scenarios Sadjadpour posed in that interview are now being asked by leaders, commentators, as well as many Iranians themselves across the word.

A regime that endures, but no longer inspires

The Islamic Republic still governs through a powerful security state anchored in the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), clerical institutions, and parallel economic networks.

Yet its legitimacy, if not efficacy, has been eroded dramatically.

The population is young, urban, educated, digitally connected, and profoundly alienated from the ideological foundations of the regime.

Protest waves in recent years, especially after the death of 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman Mahsa Amini, in a hospital in under suspicious, revealed not only social anger but civilisational fatigue with clerical rule.

Geopolitically, Iran is more isolated than at any point since the Iran-Iraq War. Sanctions, currency collapse, environmental crisis, brain drain, and diplomatic marginalisation have hollowed out national capacity.

As Sadjadpour notes, Iran is a country with G20 potential living with third-world constraints. The gap between what Iran could be and what it is has become politically explosive.

The succession question as a geopolitical marker

Khamenei is not merely a leader; he is the system’s shock absorber. His authority contains factional warfare among clerics, technocrats, security elites, and economic cartels.

Once he exits, succession will not be a constitutional routine-it will be a geopolitical event with regional and global consequences.

Sadjadpour’s five scenarios: Russia, China, North Korea, Pakistan, and Turkey, are not predictions but structural possibilities:

- Russia model: Collapse of the clerical order, followed by a nationalist strongman backed by security elites.

- China model: Authoritarian continuity with economic pragmatism and selective opening.

- North Korea model: Hardline ideological closure under clerical or dynastic rule.

- Pakistan model: Military guardianship by the IRGC.

- Turkey model: Electoral populism with illiberal tendencies.

As Sadjadpou asked: “The question I wanted to probe was whether the Islamic Republic after Khamenei would endure, transform, or implode-and what kind of system would emerge in its wake.”

The most likely outcome is not one of these alone, but a hybrid, with some form of coercive transition where the side that controls guns, money, and institutions-not ballots-wins first, and legitimises later.

Above: People take part in a demonstration to support mass rallies denouncing the Islamic republic in Iran in Paris on January 11, 2026. (Kiran RIDLEY / AFP) and via Times of Israel.

The IRGC: A State within a state

The IRGC is Iran’s most decisive geopolitical actor. It controls missiles, proxies, cyberwarfare, energy networks, smuggling routes, and major construction and trade sectors.

Yet it is not unified; it is a federation of rival networks-generational, ideological, and commercial.

And Khamenei has managed these with rivalries Machiavellian aplomb.

Without him, some have argued, these factions could, and will, become destabilising.

Therefore, succession is not just about clerics choosing a new supreme leader. It is about whether the IRGC accepts clerical supremacy, replaces it, or fragments into competing power centres. In geopolitical terms, Iran risks shifting from a centralised ideological state to a praetorian system where generals, cartels, and regional bosses’ bargain over power.

Regional power without a vision

Iran’s foreign policy is still defined by the so-called “Axis of Resistance”: Hezbollah, Iraqi militias, Syrian factional alignment, Yemeni Houthis, and confrontation with Israel and the United States.

For Khamenei, this is not a strategy, but rather, it is a faith.

But geopolitically, it has weakened Iran more than it has strengthened it. The network is costly, increasingly contested, and as we saw in the middle of last year following the Twelve-Day War, much less effective than those in Tehran would have hoped.

A post-Khamenei leadership will face a stark choice: continue ideological confrontation or redefine national interest. Most Iranians understand that hostility toward the West and especially the U.S., has been economically catastrophic.

Yet transitions rarely, if ever, reflect popular will. They reflect power balances. If security elites benefit from confrontation, confrontation will continue, even if Iranian society in general wants normalisation.

In our increasing multipolar world, Iran could theoretically hedge between China, Russia, and the West. But as Sadjadpour argues, no country has paid a higher price for obsessively opposing the power of the United States.

Even the rivals of Washington – from Vietnam to Turkey – have benefited from selective partnership. Iran’s isolation is a self-inflicted wound.

Nationalism versus democracy

One of the most dangerous illusions in Western thinking is that the fall of clerical rule automatically leads to democracy. History says otherwise. Often, authoritarian collapse produces another version of authoritarianism that is more brutal, sometimes more secular, sometimes more nationalist.

Iran is fertile ground for grievance-driven nationalism: resentment over sanctions, humiliation, regional wars, and perceived Western hostility.

A future strongman could easily mobilise this into a new authoritarian creed, albeit less religious and more nationalist, but no freer.

Democracy, by contrast, requires organisation, leadership, compromise, and institutions-things Iran’s fragmented opposition still lacks.

As Sadjadpour puts it, authoritarian transitions are not popularity contests; they are coercive competitions.

Source: YouTube.

Monarchy, memory, and myth

The idea of restoring the ousted Pahlavi monarchy remains emotionally powerful for some Iranians, especially in diaspora, and with some US media outlets. But geopolitically and structurally, it lacks the internal institutional backing that made Spain’s restoration possible. Without support from existing power centres, symbolic legitimacy alone is insufficient.

More importantly, nostalgia is not a political program. The real question is not who ruled before 1979, but who can build a viable state after the current system cracks.

Conclusion: A very dangerous interregnum

Iran has entered what some historians call an ‘interregnum’: The old order is dying, but the new one has not yet been born. Such periods are marked by instability, authoritarian temptation, and above all, geopolitical risk.

Regardless of the outcome of these nationwide protests, the Islamic Republic may endure longer than many would expect or for that matter, would like.

But it will not endure unchanged.

The post-Khamenei era will test whether Iran becomes:

- A nationalist autocracy,

- A pragmatic dictatorship,

- A militarised state,

- An illiberal democracy,

- A constitutional monarchy-headed republic.

For now, the balance of power favours coercion over consent. Iran’s society is ready for freedom, but its institutions are still built for command and control.

The tragedy, along with the danger, is that history suggests the side with the most guns usually writes the first chapter of the next regime- usually in blood.

Only later does a society get a chance to revise it.

*Karim Sadjadpour is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where he focuses on Iran and U.S. foreign policy toward the Middle East. Recently, Sadjadpour wrote an essay for Foreign Affairs, titled “Autumn of the Ayatollahs: What Kind of Change is Coming to Iran?”