Over the past 10 years, the value of agricultural land in Romania has increased 4.2 times, reaching €8,700 per hectare in 2024, 36% higher than in France, according to the latest data published by Eurostat. At the European level, Romania ranked in the middle in 2024, with arable land prices ranging from €4,825/ha in Latvia to €201,263/ha in Malta.

An economic analysis of an emerging market vs. a mature market by Alinda Bănică Business Consultancy

The Eurostat statistics have recently been made public, sparking renewed speculation about the supposed superiority of Romanian soil quality or a potential overvaluation of the local market.

However, an analysis conducted by the independent consultancy firm Alinda Bănică Business Consultancy offers a different interpretation: the price difference is not due to agricultural value but to market maturity. Alinda Bănică Business Consultancy is an independent advisory boutique founded 19 years ago by Alinda Bănică, a professional with over 20 years of experience in banking, finance, and management consulting. The company is a partner to Romanian agriculture, providing know-how and expertise in this industry, both through business consulting and insurance advisory services.

Recently, information has emerged regarding the price of agricultural land in Romania and comparisons with France, with the discussion focusing on the fact that Romanian land prices have surpassed those in France. Allow me to start analysing this topic (without claiming to be exhaustive) with one note: we have had access to a large amount of information in recent years, and we like numbers.

The illusion of numerical objectivity is something I want to emphasise from the start, using a simple example from the financial world: leasing companies must report the number of new contracts they conclude in a year. One company reports exactly that—the number of new contracts concluded that year—while another, when reporting this figure, also includes contracts that were assigned to new users, even though those contracts are not new at all. We then have a pseudo-quantitative understanding; the numbers are internally correct but do not support a legitimate comparison,” says Alinda Bănică, Principal Consultant at Alinda Bănică Business Consultancy.

Different prices, different markets: factors influencing the value of agricultural land

Alinda Bănică highlights the factors that influence the value of agricultural land: national factors (such as legislation), regional factors (such as climate and proximity to logistics networks), and productivity factors (such as soil quality, slope, drainage, and irrigation level).

Market dynamics are also important: prices are influenced by supply and demand, as well as by rules governing foreign ownership.

“It should also be considered that farmers are not the only players in this market: prices are also driven up by other actors who wish to use the land for non-agricultural purposes (for example, developers or investors). In France, for instance, between 2010 and 2020, the number of farms decreased by 21%, with 2021 marking a peak in the number of hectares sold for urban development (33,600 ha),” adds Alinda Bănică.

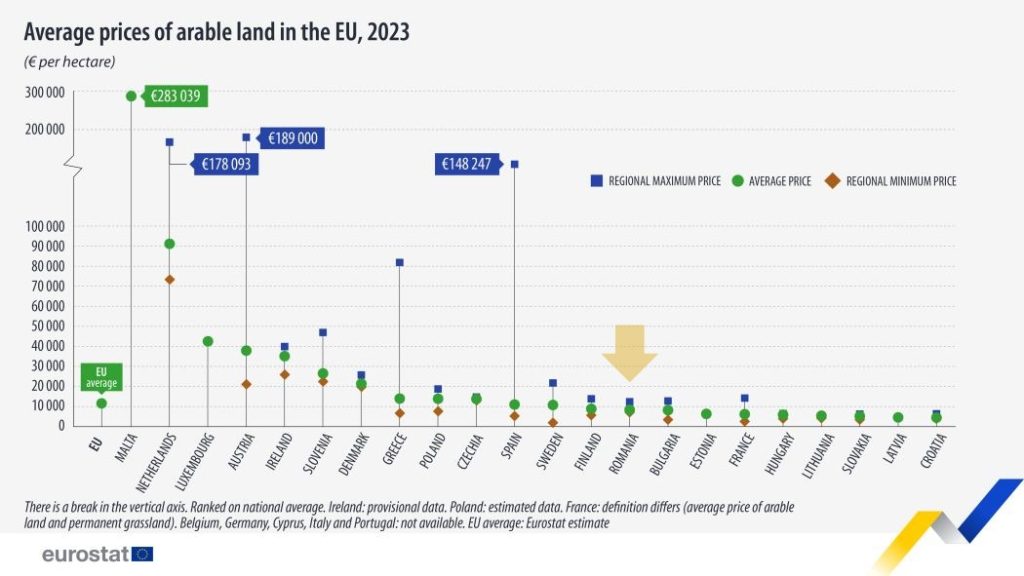

- Agricultural land prices in the EU[1]

In 2023, the average price of one hectare of arable land in the European Union was €11,791, approximately 90 times the average annual rental value of €131 per hectare.

An analysis of the 22 EU member states for which data is available reveals significant differences between countries. Croatia recorded the lowest average price at €4,491 per hectare, while Malta had the highest, at €283,039 per hectare. The very high land prices in Malta are explained by the minimal supply of agricultural land and intense pressure from alternative land uses.

At the regional level, the highest arable land prices were recorded in the Austrian Wien region, where the average price was €189,000 per hectare. At the other end of the spectrum, the Övre Norrland region in Sweden had the lowest average price, at €1,951 per hectare.

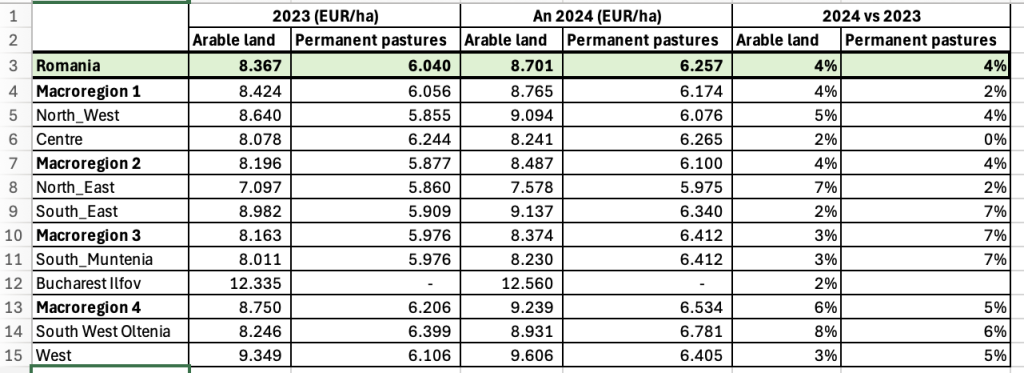

- Agricultural land prices in Romania

The average price of one hectare of agricultural land in Romania was approximately €8,370/ha in 2023, rising to around €8,700/ha in 2024.

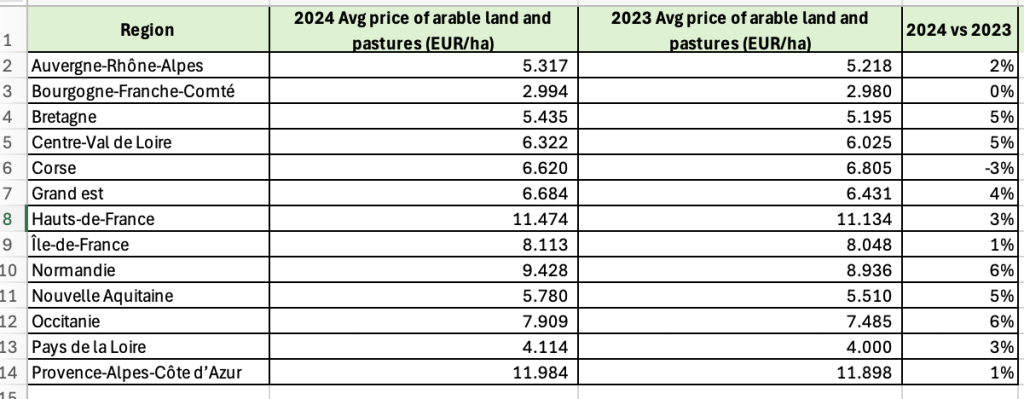

- Agricultural land prices in France

The analysis by Alinda Bănică Business Consultancy shows that the price of one hectare of land in France was €6,000 ten years ago, while in Romania it was only €2,000 (the average price of agricultural land in France in 2024 being €6,400/ha, an increase of 3.2% compared to the previous year).[2] In France, prices have remained relatively stable over the past 10 years, while in Romania they have risen.

The fundamental difference between Romania and France is not primarily due to soil quality or agricultural productivity (although these factors are undoubtedly important at a given point), but to the stage of maturity of the land market.

“A little over ten years ago, in my role as a consultant, I handled the country’s first transaction involving a bank loan secured by agricultural land—a €10 million deal. On that occasion, I discovered that at the time, there was only one real estate appraiser who knew how to value agricultural land; the rest used the same methods as for regular land. That is why values were primarily around €2,000/ha. Do you think farmers were aware of this?” adds Alinda Bănică, Principal Consultant at Alinda Bănică Business Consultancy.

- Romania: an emerging market in the process of alignment

Another factor that makes such a comparison unfair is that the land was fragmented, and complete titles did not exist. “I know investors who spent a decade—or even longer—working separately to regularise ownership documents and consolidate the land they held,” adds Alinda Bănică.

France, by contrast, is a mature market, with decades of history in which agricultural land prices primarily reflect: agrarian yields, the level of subsidies, and strict regulations on land use.

Romania, on the other hand, is an emerging market that, after 1990, underwent a rapid process of privatisation, liberalisation, and later, European integration. In this context, agricultural land was not perceived solely as a production factor but increasingly as an investment asset. Romania started from an artificially low price level, influenced by post-1990 legal uncertainty, extreme land fragmentation, and limited access to financing.

“EU accession significantly reduced these risks. For investors, Romanian agricultural land became an asset with the potential for rapid catch-up, leading to a price adjustment. In other words, it was not France that became cheaper; Romania went through a rapid alignment process toward a European perception of land value,” adds Alinda Bănică.

- Farm structure: a key structural difference

In Romania, there are approximately 2.86 million farms, with an average size of 4.39 hectares per farm (2023 data, the most recent available). In France, the number of farms is around 350,000, with an average size of 93 hectares (2023 data[3]).

Most Romanian farms are small; over 90% are under 5 hectares, the highest proportion in the EU.[4]

- Total farms: 2.859 million (not all farmers are “active”), using 12.55 million hectares of agricultural land in 2023.

- Slight decrease compared to 2020 (2.887 million farms, average 4.42 ha).[5]

- Farms under 5 ha: 90% of Romanian farms.

- Farms over 50 ha: only 1% of farms, but they cultivate over 50% of the total agricultural area.[6]

Beyond the numbers, in practical terms, Romanian farmers have invested heavily in land consolidation in recent years, and farms of several hundred hectares have become increasingly common in the country’s agricultural landscape.

France has lost 40,000 farms over the past four years, with a trend toward larger farm sizes.[7] : 349,600 farms in 2023 compared to 389,000 in 2020. About 10% of farms cultivate more than 200 hectares, accounting for a quarter of the total farmland.[8]

In France, starting in 2023, under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) regulations, subsidies are granted only to farmers considered “active.” (Romania is gradually aligning with these regulations as well).

An active farmer is a person who actually carries out a verifiable agricultural activity, both economically and professionally, and does not simply own land. This is also why Romania has so many farmers, many of whom are inactive.

-

- Land ownership structure and demographic pressure in France and Romania[9]

In France, individual agricultural operators continue to represent the majority of participants in agricultural land transactions, although their share is decreasing. At the same time, the demographic structure of the agrarian sector indicates significant pressure on the land market, with approximately 60% of farm managers over 50 years old. In Romania, over 44% of farmers are over 65 years old, and less than 10% of active farmers are under 40.[10]

According to the analysis conducted by the independent consultancy firm, this reality naturally creates potential for farm succession and land mobility. The essential difference with Romania, however, is that in France, this transition is channelled and regulated through clear public policies aimed at maintaining agricultural land use, facilitating the entry of young farmers, and limiting speculative capital.

Thus, although demographic pressure exists, it does not translate into pronounced price volatility but rather into a controlled process of agricultural restructuring.

III. Capital inflow and the role of non-agricultural investors

In Romania, a significant portion of the demand for agricultural land has come from investment funds, individual investors with surplus capital, and companies outside the farming sector.

In a context of high inflation and financial volatility, agricultural land has been perceived as a real asset, offering protection against inflation and serving as an alternative to the urban real estate market or financial instruments.

In France, access to speculative capital is much better channelled and limited, precisely to protect the agricultural use of land (see also the “Sempastous” law from December 2021[11])

- Land fragmentation and low liquidity

A characteristic feature of Romania is the extreme fragmentation of agricultural land. Most transactions involve small plots; however, when a consolidated, large, well-located plot comes to market, the price increases considerably. As a result, the statistical average is influenced by rare transactions with very high values. For example, in 2024, according to MADR, the transaction with the highest value for arable land was 3,160,000 EUR for a plot located in Ariceștii Rahtivani, Prahova County.

In France, the market is much more liquid, and the land ownership structure is more balanced, which reduces price volatility.

In Romania, more so than in France, agricultural land prices often include a component unrelated to agriculture: the anticipation of a change in land use.

Land located:

-

- near cities,

- close to infrastructure,

- in areas with logistic or residential potential

- incorporates in its price a real estate option value. In France, such conversions are strictly controlled, which limits speculation.

- Why France remains stable

Price stability in France is the result of consistent and substantial institutional intervention (see the law discussed above, whose primary purpose is to protect the traditional family farm structure, facilitate access to land for active farmers, and limit speculation and excessive, uncontrolled concentration of agricultural land[12]).

Through organizations such as SAFER (Sociétés d’aménagement foncier et d’établissement rural), the French state:

-

- has preemption rights,

- can block speculative transactions,

- can adjust prices deemed excessive,

- treats agricultural land as a strategic asset rather than a freely tradable financial asset.

VII. Is the current level sustainable in Romania?

Rising land prices raise questions about sustainability.

The main risks identified by Alinda Bănică Business Consultancy are:

- A fundamental disconnect between land prices and agricultural profitability, if efficiency practices such as land consolidation and the adoption of appropriate technologies are not continued (small producers do not achieve efficiency, and yields may be low for those entering the market at current prices).

- Dependence on European subsidies.

- Lack of financial literacy of the farmers.

- Tempered investment appetite in a context of high interest rates and still limited financing periods.

- Accelerated ageing of the agricultural workforce. This is a significant issue at the EU level, where the average age of farmers is 57, prompting the European Commission to propose expanded support for young farmers through larger CAP allocations and targeted fiscal measures. In Romania, the situation is even more pronounced, with over 44% of farmers over 65, increasing the risk of farm fragmentation and loss of competitiveness in the absence of planned generational transfer.

- The proposed 2028–2034 multiannual EU budget reduces the share of CAP and cohesion funds from approximately 62% to 44% of the EU budget [13], even though the total nominal budget increases[14]. There is a strong consensus in the economic literature [15] that direct CAP subsidies are capitalised into land values: a significant portion of subsidies flows into rents and land prices, not just into farmers’ incomes. The direction is clear: substantial and persistent cuts to direct subsidies, in the absence of other positive shocks, will put downward pressure on, or at least cap, the prices of agricultural land in Romania, particularly in weaker regions.

- The EU-Mercosur agreement. The logic of this agreement is as follows:

- The agreement gradually reduces Mercosur tariffs on EU exports of cars, auto parts, machinery, chemicals, wines, spirits, etc., benefiting Germany significantly in these sectors.

- In return, the EU opens its market to beef, pork, poultry, sugar, rice, honey, soy, and other South American agricultural products through quotas and tariff reductions.

- Result: the European industry (mainly German) gains on processed goods exports, while European farmers face cheaper food produced at lower costs (land, regulations, inputs). In short, the Mercosur discussion represents the same “fault line” as the CAP budget debate: Berlin & co. seek industrial competitiveness and cheaper food, and the political and economic cost is shifted to European farmers—including those in Romania[16].

The most likely scenario is not a sharp decline, but:

- In the absence of continued efficient consolidation of agricultural land at the same pace as before, a modest short-term increase in prices is expected due to infrastructure improvements and demand.

- However, we must also consider a subjective factor influencing these price increases: the natural land consolidation process. For certain farmers, consolidating land has a strategic value greater than the price difference, and they are willing to pay a premium for plots that complement their existing holdings.

- In this context, there are situations where the price does not strictly reflect the average economic value of the land, but rather opportunistic-speculative factors related to location and consolidation objectives.

- An increasingly pronounced differentiation (already visible) between high-quality, consolidated land and less productive or fragmented land.

VIII. Conclusion

The difference between Romania and France does not currently reflect an agricultural superiority of Romania, but rather reflects differences in economic cycles, regulations, and investment behaviour.

Romania has undergone a decade of accelerated capitalisation of agricultural land, while France is in an equilibrium phase.

This difference tells a story about markets and contexts more than it does about the soil’s inherent value as a resource.

About Alinda Bănică Business Consultancy

Alinda Bănică Business Consultancy is an independent advisory boutique founded 19 years ago by Alinda Bănică, an entrepreneur and professional with over 20 years of experience in finance (insurance, leasing, banking, management consulting).

The company provides business consulting to Romanian companies with various ownership structures, securing financing totalling over €190 million over time, and offering customised consulting and insurance audits. Its portfolio includes businesses across diverse sectors and industries, ranging from IT&C, construction, and pharma & medical to transport and agribusiness.

Alinda Bănică Business Consultancy is a partner to Romanian agriculture, bringing know-how and experience in the industry, both in business consulting and insurance advisory services. Alinda Bănică coordinated Romania’s first bank financing secured by agricultural land and designed and financed the country’s first agricultural land sale-and-leaseback transaction with a German investment fund.

With extensive experience in agribusiness and commodity markets, she organised the first seminar in Romania dedicated to commodity hedging, in partnership with INTL FCStone (CME Group), and represented Romania as a speaker at international conferences on cereals, vegetable oils, and organic farming.

- [1] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Agricultural_land_prices_and_rents_-_statistics

- [2] https://www.le-prix-des-terres.fr/carte/terre/

- [3] https://www.pleinchamp.com/actualite/en-4-ans-la-france-a-perdu-40.000-exploitations

- [4] https://www.agroberichtenbuitenland.nl/actueel/nieuws/2025/01/22/romania-still-counts-2.8-million-small-farms—largest-number-in-eu

- [5] https://www.dutchromaniannetwork.nl/en/romania-still-has-2-8-million-small-farms-the-largest-number-in-europe/

- [6] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Farms_and_farmland_in_the_European_Union_-_statistics

- [7] https://www.pleinchamp.com/actualite/en-4-ans-la-france-a-perdu-40.000-exploitations

- [8] https://www.lafranceagricole.fr/economie/article/884669/des-fermes-avec-davantage-d-hectares-et-d-ugb-entre-2020-et-2023

- [9] https://www.le-prix-des-terres.fr/carte/terre/

- [10] Potrivit Clubului Fermierilor Români (CFRO)

- [11] The “Sempastous” law is a French law adopted on December 23, 2021, which introduced a regime of administrative control over transfers of shares and equity interests in companies that own or use agricultural land. The main purpose of the law is to regulate the agricultural land market and access to land more strictly, especially when the land is owned by corporate structures (companies) rather than individuals.

- [12] https://www.ma-propriete.fr/en/blog/le-controle-des-cessions-de-parts-de-societes-agricoles-la-loi-sempastous

- [13] https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2025/07/17/ringfenced-but-reduced-eu-commission-shrinks-agriculture-share-in-record-budget

- [14] https://www.delorscentre.eu/en/publications/detail/publication/ripe-for-reform-whats-in-the-eu-budget-proposal

- [15] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837723003666

- [16] https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20251218-what-to-know-about-the-eu-mercosur-deal