The German expression “Das Recht des Stärkeren” translates roughly as “Might makes Right.” We no longer live in a rules-based order. We live in a world where – if you’re bigger than the rest – you take what you want. That’s the best rationalization for why the US is pushing Ukraine to make peace with Russia. After all, the argument is that if Ukraine doesn’t make peace today, it has to make peace on worse terms tomorrow, having lost more territory and lives. The inviolability of Ukraine’s borders – territorial integrity – has de facto been subordinated to Russia’s greater military might. This also explains current saber-rattling over Greenland and the US intervention in Venezuela.

The point of this post isn’t whether this is right or wrong. I’d obviously much rather go back to the rules-based order. My point – instead – is that the EU isn’t adapting to the new status quo. The current outrage over Greenland is the latest example. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four years ago, the EU has – again and again – failed to project strength and resolve: (i) it looked the other way as Greek ship owners sold lots of oil tankers to Putin for his shadow fleet, giving Russia the means to keep exporting oil on its own terms; (ii) it ignored rampant transshipment of Western goods to Russia from all across the EU; and (iii) most recently, it failed to use Russia’s frozen reserves to fund Ukraine. The cumulative bill for these failures is high and will grow as long as the EU doesn’t adapt. Greenland is just the latest symptom of this EU dysfunction. It should be clear that the status quo isn’t working. Deep change is needed, which in my view requires a Pax Germanica, by which Germany asserts itself more within the EU.

In this post, I’ll run through these EU failures, which – in my view – are what greenlighted US saber-rattling over Greenland:

-

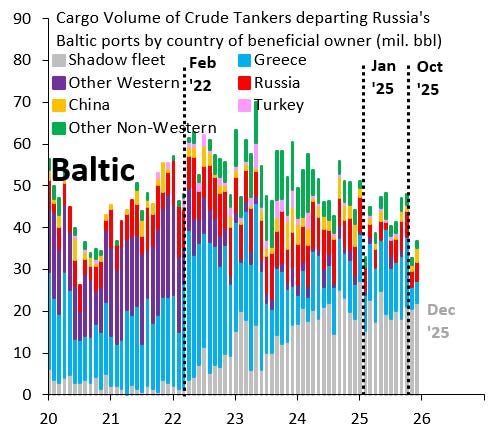

Russia’s shadow fleet of oil tankers is a monster of the EU’s own creation: Ben Harris and I have shown that half the vessels in the shadow fleet were sold to Russian interests by Greek ship owners. The gray bars in the chart below show that the shadow fleet makes up half of all tanker traffic out of Russia’s Baltic ports. The EU can shut this down if it wants to or – at least – severely curtail it. The reason this isn’t done basically falls under “this would violate the rules-based order.” That order went out the window years ago, so this is backward-looking. Confronting Putin and staring him down – which is what clamping down on the shadow fleet would be – is uncomfortable and scary. But there’s no other way. If this doesn’t happen, Russia, China and the US will keep bullying the EU.

-

Four years of looking the other way on transshipments to Russia: the black line in the chart below shows Germany’s direct exports of cars and parts to Russia, which fell sharply right after the invasion. But exports to the Caucasus, Central Asia and Turkey rose substantially right around the same time, as the orange line shows, which is highly suggestive of transshipments to Russia. Once you factor in transshipments, exports of cars and parts from Germany to Russia really haven’t fallen much, if at all. Unfortunately Germany isn’t alone in this. Four years after the invasion, these transshipments are rampant across much of the EU.

-

Failure to seize Russia’s frozen FX reserves: using Russia’s frozen reserves to fund Ukraine would have been a powerful signal to Russia (and others) that the EU is willing to take risks and punish murderous regimes. This would have had a deterrent effect, while there is no basis whatsoever to think this would have hurt the reserve currency status of the Euro. In fact, in my opinion the opposite is true. It’s damning that reserve managers didn’t shift out of the Dollar into the Euro in a years with as much policy chaos as 2025. The fact that this didn’t happen, as the chart below shows, suggest that EU weakness in the face of external threats is in fact hurting the Euro. EU assertiveness would boost its reserve currency status.

We all want a stronger, more assertive EU. The problem is how to get there. Think back to the discussions in December around using Russian reserves for Ukraine. That didn’t happen because France and Italy opposed Germany. Would that have been true if the ECB hadn’t in 2022 intervened to cap Italian yields and introduced the TPI anti-fragmentation tool? Of course not. High-debt countries would be struggling with sky-high yields and focused on fixing their broken public finances. The EU’s dysfunction on geopolitics thus traces back to the ECB, where Germany has allowed itself to be cowed by high-debt countries. In my opinion, the only way this will ever change – and the only way in which the EU can become a serious geopolitical actor – is if Germany credibly threatens Euro exit. That will be the start of something good. After all, the Euro is just a series of exchange rate pegs. If these pegs and the ECB are keeping the EU from being as strong as it needs to be, they’re past their sell-by date.