Part III: Exploring the Art World, Searching for Familiarity, Finding Muriel Franceschetti

Before the lockdown, within my first two months in Paris, I met two Americans who left a lasting impression on me.

The first was a young woman from Colorado who had just completed her studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She sat next to me on an Air Tahiti flight from Los Angeles to Paris. She had come for an internship at a nonprofit organization, working on a refugee project shaped by the murder of her father in a political conflict.

During those first weeks, we met several times, happy to explore the Paris art world together. We visited the Pierre Soulages centenary exhibition at the Louvre and the Barbara Hepworth exhibition at the Musée Rodin. Yet she left earlier than planned when the pandemic began. With people advised to work from home, there was little reason for her to remain in Paris, and she returned to Colorado to be with her sister and mother.

The second American I met was Jamie. He approached me at the Centre Pompidou, where I had just seen Bacon en toutes lettres and was wandering through the permanent collection. I was standing in front of “Le Rêve” by Matisse, a painting of a woman with her eyes closed, when he asked,

“Qu’est-ce que vous pensez de ce tableau?”

“Pardonnez-moi. What?” I replied.

“What do you think about the painting?” he repeated in a deep voice, smiling.

“Oh, you speak English?” I said.

At the time, my mind was elsewhere on my failed American dream, the expiration of my U.S. work visa, and the rejection of my green card application. USCIS told me I could appeal and submit more evidence, but I had nothing impressive left to offer. Intuitively, I knew that the letter from Emil Wyss, the former Consul General of Switzerland in Los Angeles, who had met me at the Ruth Bachofner Gallery in Santa Monica, would not be enough. Most people, I suspect, would have introduced themselves in a very different way.

We talked for a while and then exchanged numbers. When Jamie walked away, I noticed he was wearing a skirt. I was momentarily confused. Was it a fashion statement? And wasn’t Jamie a woman’s name? I soon learned that Jamie was a crossdresser, the child of a minister’s family from the Midwest who fully accepted and loved him. He had worked in a musical instrument store in Seattle before learning French through an art appreciation course in Aix-en-Provence.

We first met again at Les Deux Magots, where I had once also met artist Maya Mercer’s mother for coffee. “I’m so sorry my country didn’t give you a green card after twenty-five years,” Jamie told me. Afterward, we crossed the street to the Église de Saint-Germain-des-Prés to admire the blue ceiling of the nave, where they sometimes hold classical concerts. We spent the afternoon at the Picasso Museum, attracting attention both because of his skirt and his passionate, animated way of talking about art.

Then the lockdown arrived. Jamie stayed in his tiny apartment in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, while I remained in mine in the 10th arrondissement, rented from a Russian-American violinist. After restrictions lifted, we met again, sitting along the Seine and savoring a regained sense of freedom. Later, we went to Montmartre, my first time experiencing it not as a visitor, but as someone who now lived in France.

When Jamie also decided to return to the United States earlier than planned, like the young woman from Colorado, I felt a deep sense of loss. There were hardly any American tourists in Paris, and the American Center for Art and Culture, where I had hoped to see Lita Albuquerque’s exhibition 20/20: Accelerando, had not reopened.

This absence echoed something many people failed to understand about my identity. I had not come to Paris from Germany, but from the United States. Just as Jamie was born male but felt more like a woman, I was born in Germany but felt more like an American. I had spent a significant portion of my life in the U.S., studied American Studies at the John F. Kennedy Institute in Berlin, and was an intern at the American Academy in Berlin.

Yes, my mother lives in Germany, but she was born in Galați, Romania, as the child of refugees. Her parents came from Bessarabia. My grandmother never learned to write German properly, and they all kept their own accents and way of cooking.

From early on, I had a fascination with American culture. It always seemed that more could happen there than anywhere else for someone with my background. I am not from a typical family. I come from a family that had a child with a severe intellectual disability and epilepsy, in a country that was not very accommodating. In fact, Germany has a history of systematically killing children like him, and that made a profound difference. I experienced Germany as a place with little tolerance, whether toward my sibling, toward my résumé after I studied in the U.S., or toward my entire life path. I was not a square, but a fluid, creative, and sensitive soul.

In contrast, the United States, or rather California, offered me understanding. A college teacher took a deep interest in my story as the sister of a person who could not express himself verbally or in writing in the way most people do. Things may have changed in Germany on the surface since then, but that cannot undo the fact that I have become an international person with a strong sense of freedom and gender equality.

And so I found myself thinking about the Côte d’Azur, its orange and lemon trees, bougainvillea, palm trees, and water. The Pacific Ocean and the California landscape and its seagulls had shaped my life for many years, and so were its sunsets.

For one month, I stayed in a small but charming studio on the Cimiez hill, near the Excelsior Régina Palace, the Belle Époque residence built for Queen Victoria, and close to both the Marc Chagall National Museum and the Musée Matisse. This proximity gave me a sense of continuity. It reminded me of an earlier moment at Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage at LACMA in Los Angeles, where I met Chagall’s granddaughters, Bella Meyer and Meret Meyer-Graber. LACMA, after all, had been the first museum I visited when I moved to Los Angeles in 1987.

French artist Muriel Franceschetti/ MULIA at Confort 2, her studio and exhibition space in Nice (2020). Photo: Simone Suzanne Kussatz / ARETE.

It was during this period, on my way to walk from MAMAC to Place Masséna, that I passed a storefront transformed into a temporary exhibition space, Confort 2, a former bedding store on Boulevard Jean Jaurès, where I discovered the work of Marseille-born and Paris-based photographer Muriel Franceschetti, also known as MULIA. Her exploration of the mother-daughter bond and psychologically charged works, influenced by the Cobra movement, sparked my curiosity, leading me to speak with her about her work and artistic journey.

From that, I learned that her subject matter was very well received and that it also won her recognition from prominent figures in France’s creative and cultural sectors, including Laura Estrosi, the wife of Nice’s mayor Christian Estrosi, and Robert Roux, a council representative in Nice. Franceschetti uses the space as both studio and gallery.

Simone Suzanne Kussatz: “Your figures are very colorful and imaginative. What inspired you to create them in this way?”

Muriel Franceschetti: “I was influenced by African culture. The father of my ex-husband was an art collector of African art. He had African ceremonial masks and jewelry everywhere. My work is also inspired by Jean Dubuffet and the Cobra movement.”

Simone Suzanne Kussatz: “Who or what influenced you in particular from the Cobra movement?”

Muriel Franceschetti: “My favorite artist is Karel Appel. His paintings are very easy for me to read. They resemble children’s drawings. The first thing you notice in his work is his use of color. He works with primary, raw colors. When I create my paintings, I feel as if I am writing a sentence, and the title is the period at the end.”

Simone Suzanne Kussatz: “You have worked as a professional photographer for more than two decades. How did you become a photographer, and how does photography influence your paintings?”

Muriel Franceschetti: “As a teenager, I always took pictures, but I then started working as a model and actress for French television series and advertising. As a model, I traveled to China, Japan, and all over Europe. I worked with an agency in Paris, where I met the American photographer Britt Erlanson. Through her, I learned a lot about photography. She realized quickly that I wanted to be behind the camera, so she gave me a car and a camera. I started taking photography seriously at age twenty-six. I first photographed actors at a drama school in Paris, which developed into my later work. In my paintings, you can still see the focus on people.”

Simone Suzanne Kussatz: “What made you switch to painting?”

Muriel Franceschetti: “Photography changed. In the past, you could defend your point of view and universe, and that is why clients came to you. Today, the market is dominated by influencers, people like Nabilla Benattia, a reality TV star. The quality of photography has declined. I was competing with young people who create works in that reality TV style, and we do not speak the same language. In 2016, I experienced burnout and was hospitalized for four days. I felt that what I produced no longer represented me. I felt nervous and anxious, and I did not like the commercial, money-driven side of photography.”

Simone Suzanne Kussatz: “And what happened then?”

Muriel Franceschetti: “In 2015, I did a painting with my daughter Lia. The day after we posted it on Facebook, we already had 400 followers. In 2016, I passed by a hangar in Paris. The door was open, and I went inside to ask if I could use the space for a photoshoot with a client. When the owner learned I was also a painter, she asked if I wanted to paint there. She said her father would be happy if someone used the space, because otherwise homeless people would occupy it. She gave me the key, and I had 800 square meters to myself without paying rent. I did a huge painting there. After that, I opened an Instagram account and uploaded an image of the large canvas. Six months later, a friend in Cannes asked if I wanted to exhibit my work at a gallery there. I thought he was joking, as I had only ten to twelve paintings at the time. Then, another gallery in Paris invited me to exhibit, but I did not go because I found the people too snobbish. Later, a gallery near Les Puces, a flea market in Paris, wanted my work. They sold it quickly, but I was unhappy because they did not tell me the prices. Every decision I make is guided by my intuition. It tells me whom I should work with and from whom I should stay away.”

Simone Suzanne Kussatz: “A year after your first painting, you created Napoleon. Can you tell me about that?”

Muriel Franceschetti: “The wife of the mayor of Nice, Laura Estrosi, wanted to buy it for her husband’s birthday because he was a huge Napoleon fan. We have kept in touch since then.”

Simone Suzanne Kussatz: “You also had the opportunity to show your work alongside other artists at the Téléthon in France. How was that experience?”

Muriel Franceschetti: “People had to bid, and the event raised more than a million euros for sick orphans. I continue to participate every year. Through this show, Robert Roux, a municipal counselor in Nice, saw my work. He told me he liked it and wanted to meet me. We spoke for two to three hours. He is an artist himself and open to new ideas. When we talked, he completely understood me, and that is why I am here.”

Simone Suzanne Kussatz: “You mentioned that your work is influenced by your unusual family. Can you talk a bit more about this?”

Muriel Franceschetti: “When I was young, my parents both worked too much, and I felt a deep loneliness. I never found my place in a school. I had good grades, but I excelled in sports. I could sprint and do long jumps, and I considered a career in sports, but I lacked the thick skin needed to succeed. I was also talented in the arts, so I turned toward that. Because my parents were often absent, others cared for me, but they never truly understood me. My parents divorced when I was eleven, but it did not change much. My father was rarely present. When I was fourteen, he was arrested and jailed for seven years for robbing a bank. He was arrested several more times after that, and I often visited him in prison. My mother was more of a woman than a mother. She had an attitude of ‘if I am here, I am here; if not, I am not.’

I met my first husband when I was sixteen. He was the first person who truly cared for me. We had my first daughter, Juliana, when I was twenty. She is twenty-seven now. My first husband was somewhat like my father. His father was somewhat autistic, but he also had a passion for African art. He taught me to look at art books and visit exhibits, and I learned a lot from him. My first husband and I divorced, but remained close afterward.

I have a very close relationship with my two daughters, who are of different ages. My artist name, MULIA, comes from our letters: Mu for Muriel, Lia for my youngest daughter, and the three letters Lia also appear in Juliana. My youngest daughter Lia and I painted my first piece, “Nous”, in 2015. She was only four at the time. She is also interested in African culture and performs African dance.

In 2007, my first husband was killed in Spain, and a chapter of my life closed. A year and a half later, I met my second husband, Alex, at a New Year’s Eve party. That evening, he said the same words to me that my first husband said the last time we saw each other. It is a mystery. My work reflects my upbringing, trauma, and family.”

Simone Suzanne Kussatz: “Thank you for our conversation.”

Since her exhibit at Confort 2 (6 July – 25 August 2020) in Nice, Muriel Franceschetti / MULIA has held several other shows, including her most recent exhibition with her daughter titled De fils en céramique at L’Atelier Franck Michel in Nice (November 1 – November 29, 2025).

Instagram: @muliapainting

MULIA, peintre, plasticienne | L’Atelier Franck Michel

A painting by MULIA, shown at Confort 2, her temporary studio and exhibition space, in Nice (2020). Photo: Simone Suzanne Kussatz / ARETE.

The works by MULIA, shown at Confort 2, her temporary studio and exhibition space, in Nice (2020). Photo: Simone Suzanne Kussatz / ARETE.

French artist Muriel Franceschetti at Confort 2 – her temporary studio and exhibition space in Nice (2020). Photo: Simone Suzanne Kussatz / ARETE.

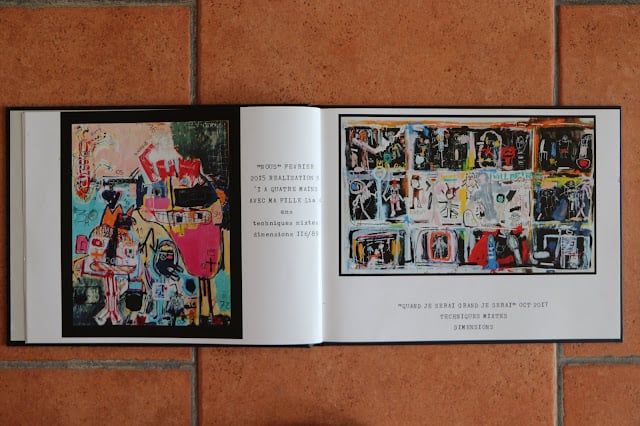

Exhibition catalog showing the work of MULIA at Confort 2 – her temporary studio and exhibition space in Nice (2020). Photo: Simone Suzanne Kussatz / ARETE.

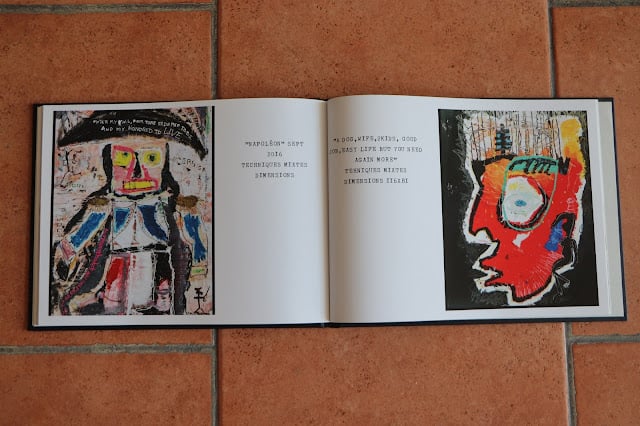

Exhibition catalog showing the works of MULIA at Confort 2 – her temporary studio and exhibition space in Nice (2020). Photo: Simone Suzanne Kussatz / ARETE.