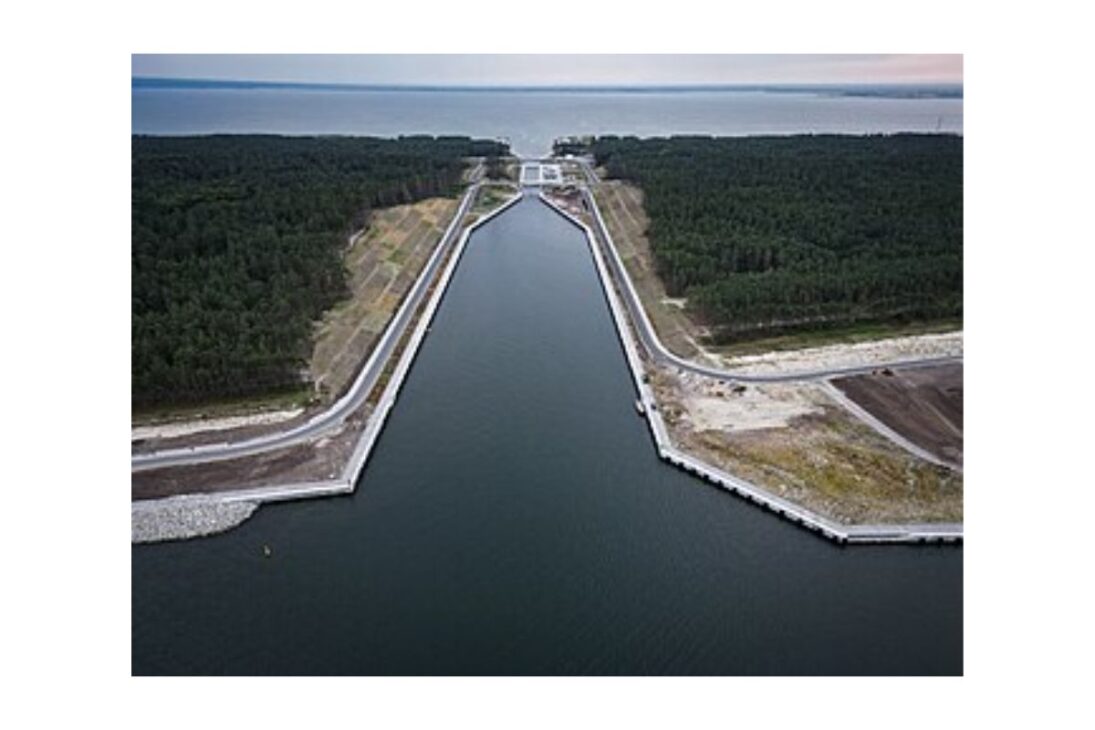

Poland opened a channel in the Vistula sandbar to avoid depending on the strait controlled by Russia in Baltisk, installed a lock to stabilize water levels, planned continuous dredging to maintain depth, and used the excavated material to build an artificial island, transforming sovereignty into a regional endeavor.

Poland decided it would no longer accept that the exit from a Polish lagoon to the Baltic Sea depended on a port located on the Russian side. Instead of negotiating, waiting, or living with uncertainty, the country opted for a physical solution: cutting a strip of sand, reshaping the seabed, and creating a new route under its own control, with a canal, lock, dredging works, and even an artificial island built with sediment removed from the seabed.

The project has become a symbol of sovereignty, but also a field of environmental, economic, and geopolitical dispute. It began in 2019, was inaugurated in September 2022, and now faces a real dilemma: to function as a cargo corridor and provide a future for the port of Elblag, it is not enough to simply open a canal. It is necessary to maintain depth, control currents, and confront criticism. about ecological risks and to prove that the investment of hundreds of millions of euros makes sense.

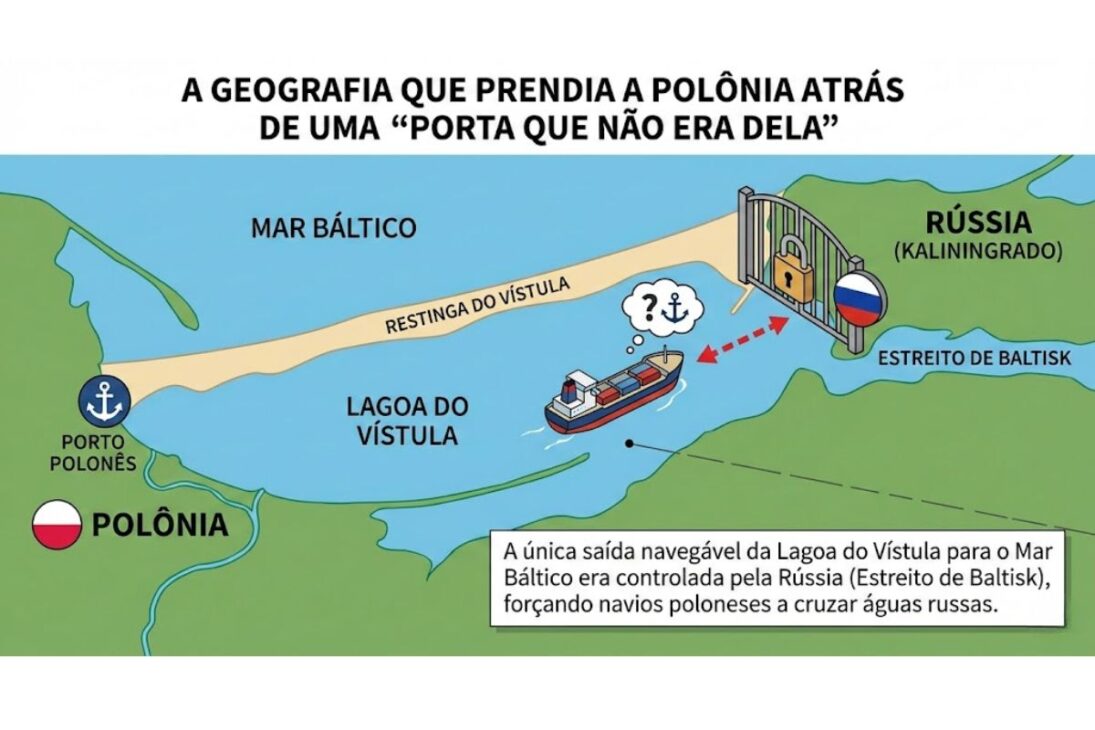

The geography that kept Poland trapped behind a “door that wasn’t its own”

In northeastern Poland, there is an extremely thin and elongated strip of land known as the Vistula sandbar. It resembles a sheet of sand separating two worlds: on one side, the open Baltic Sea, subject to wind, storms, and fluctuating water levels; on the other, the calmer Vistula lagoon, with its own dynamics, as if it were a reservoir protected by this natural barrier.

See also other features

-

The government is investing R$ 7 billion to transform two federal highways (BRs), generate 58 jobs, invest in a groundbreaking system, and accelerate construction projects that promise to change the course of agribusiness in Brazil.

-

Excavators close thousands of kilometers of artificial canals, move millions of cubic meters of earth, lower the ground on a large scale, and attempt to restore the natural flow of water to swamps drained by more than 100 years of aggressive engineering.

-

Trucks and excavators are reshaping Alpine rivers that were channeled in the 20th century, removing concrete dikes, recreating natural meanders, and attempting to reverse decades of flooding caused by rigid construction and forced straightening.

-

A new era in construction is retiring the “thick wall”: VIP 4-inch panels that insulate like 12-inch panels are revolutionizing renovations, saving energy, and freeing up space — but they require surgical precision and care that few master.

The lagoon is divided between two countries. Part is Polish and part is Russian, because the surrounding territory includes the Kaliningrad region. However, the major bottleneck wasn’t “who has the water,” but rather “who controls the outlet.” For decades, there was only one natural navigation route connecting the lagoon to the open sea: the Baltisk Strait. The problem is that it lies entirely on the Russian side. Direct result: any ship leaving Polish ports within the lagoon and wishing to reach the Baltic Sea needed to cross Russian territorial waters.

The historical and political weight of relying on a Russian corridor.

This dependency seems like a technical detail when relations are calm, but it turns into a nightmare when politics sour. The scenario was compared to a backyard with a single exit gate that’s on the neighbor’s property: on paper, the neighbor says you can go through, but the key isn’t yours.

After World War II, the territorial division consolidated the situation. With Kaliningrad in the Soviet sphere, the strategic passage was on the other side. There were formal agreements allowing the transit of Polish vessels, but the logic itself was troubling: Why does a country need permission to leave its own waters? In practice, simply increasing procedures, requirements, and restrictions was enough to make access “conditional” and insecure.

Elblag: the port that existed in the lagoon, but had no guaranteed sea access.

The most frequently mentioned Polish port in this story is Elblag. It lies within the same hydrographic system as the Gulf of Gdansk, but has always been at a disadvantage due to its dependence on the “gateway” of Baltisk. When a port survives on trade, it needs a guaranteed, predictable outlet, free from the risk of political blockade.

Without its own route, Elblag was trapped in a centuries-old dilemma. The region watched other centers grow with direct and reliable routes, while its own route depended on third parties. The canal became an attempt to correct a structural delay.It’s not just a beautiful piece of map.

The 2019 decision: Poland begins digging to gain sovereignty.

In 2019, Poland began construction of the canal across the Vistula sandbar. The image seems simple: cut sand and voila, seawater enters, lagoon water exits. But the real project involved much more than just digging a hole. The port of Elblag is about 14 miles by water from the new opening, and the entire route needed to be navigable and reliable.

As soon as Poland started digging, it entered a point of no return. A canal of this type needs to withstand storms, currents, erosion, and the constant conflict between two bodies of water with different rhythms. The project became a re-engineering of the environment., not just a shortcut.

The most crucial technical aspect of the project is the lock. If the sea and the lagoon were always at the same level, a direct cut would suffice. However, the Baltic Sea is open and reacts to winds and storms, changing its level and current. The lagoon is more stable, with its own flow and level.

If you open a narrow passage without a lock, nature tries to “equalize” the levels on its own. In a narrow corridor, this becomes a strong, unpredictable, and potentially dangerous current. Ships don’t need a lottery to get through; they need predictability. The lock works like a sealed chamber: the ship enters, the gates close, the water level is adjusted to equalize the exit side, and only then does the second gate open. It is a hydraulic elevator that transforms an unstable crossing into a daily crossing.

The reason for choosing the location: to cut where it’s narrowest to reduce cost and conflict.

Poland did not cut into the sandbar at any point. The canal was planned in the narrowest part to reduce the amount of earth removed and, consequently, the total cost. Less excavation means less money spent and also fewer complications in environmental licensing and ecological compensation.

The reasoning was pragmatic: to choose the point where the project would have the best chance of moving forward within the rules and with the least risk of legal obstacles. Engineering here is also political engineering.Because where you dig changes the intensity of protests, lawsuits, and environmental demands.

The cost that exploded: from 190 million to 420 million euros.

The project was initially estimated at around 190 million euros, but the final cost rose to approximately 420 million euros. This fueled obvious criticism: “why pay hundreds of millions for a cut that looks narrow and shallow?”.

The central argument is that the canal was not designed for mega-ships, nor to become the “new Suez.” It was designed for relatively smaller vessels, with a length of around 330 feet, a width of about 66 feet, and a draft of approximately 13 to 15 feet. The goal was not to dominate global trade, but rather to make a specific route functional, predictable, and under Polish control.

The big controversy: disturbing the seabed isn’t just disturbing the sand.

One of the most serious criticisms is environmental. The lagoon doesn’t just have sand at the bottom. It has accumulated sediments containing phosphorus, associated with sources such as sewage, livestock farming, and fertilizers. While this material remains deposited, the impact can be “quiet.” The risk arises when dredging and changes in current stir up the bottom and put these chemicals into circulation.

The most frequently cited fear is the intensification of cyanobacteria, considered more toxic in the lagoon than in the open sea. The concern is that the project will cause imbalances that are difficult to reverse, because with water there is no “fixing it later” as with a bridge. If the environmental calculation fails, the return on investment can be slow and expensive.

Russia on the back: from environmental arguments to military fears

Russia opposed the canal and continues to criticize it. One argument is that the canal could allow, at least in theory, the entry of NATO-linked military vessels into the lagoon, bypassing Russian installations in Baltisk and creating a risk for Kaliningrad.

There were also suspicions in Poland itself that the project might have military motivations, with speculation about defense infrastructure in Elblag. The counter-argument is the physical limitation: the lagoon is shallow, which reduces the practical military potential. Still, The canal has become a geopolitical symbol because it removes Russia’s power as a “gateway.”even though Russia still has regional weight.

The paradox of depth: canal ready, lagoon shallow, ship runs aground.

The channel was built with a depth of approximately 16 feet, allowing ships with a draft of up to about 15 feet to pass through this initial stretch. However, afterwards, the ship enters the lagoon, which has an average depth of 7 to 10 feet and a maximum depth of around 17 feet.

This creates a paradox that has become ammunition for critics: the ship crosses the channel without a problem and could run aground soon after. In practice, large vessels avoid the route because the risk of scraping the bottom is real. The “new gate” may open onto a passage that is not yet fully prepared.

The real bottleneck wasn’t the sea, it was the end of the road: the Elblag River.

For the route to be truly useful to Elblag, the final stretch needs to be deepened, especially a section on the Elblag River that is about 2950 feet long. This segment has become the most stubborn bottleneck. The work has stalled due to disputes and bureaucracy, delaying the promise of a real commercial corridor.

Only in January 2024 did the new government under Donald Tusk indicate that it would commit to completing the remaining section. The plan cited is to maintain the waterway with a depth of approximately 16 feet along its entire length, with a width varying roughly between 66 and 197 feet, allowing vessels up to approximately 328 feet in length and with a draft of 15 feet to reach the port. In other words, the project needs a “second phase” to fulfill its promise.

Continuous dredging: the canal is not a finished project, it is an ongoing project.

Even with initial dredging, storms, river sediments, and constant seabed movement rapidly reduce the depth. If Poland does not maintain the dredging, ships will again scrape the bottom, and the route will become useless.

The solution mentioned involves a dedicated dredger, built to operate continuously. The reasoning is simple and expensive: opening it is an expense, maintaining it is another recurring expense. Without maintenance, the canal ceases to be a waterway and becomes a geographical scar.

Dredging and logistics: underwater vacuum cleaner and piping to the island.

Poland has commissioned a dedicated dredging vessel from a Finnish company, specifically designed for depth maintenance work.

The dredger was launched on September 19, 2023, and is described as a robust, wear-resistant machine, built for the lagoon’s conditions.

It acts like a giant underwater vacuum cleaner: it sucks up sand, silt, and gravel, pumps it into a compartment, and transfers the material through piping for land reclamation. In this case, for the artificial island. This creates a cycle in which the bottom is cleaned and the excavated material immediately becomes “raw material”.

The artificial island: 445 acres, 10 feet above sea level, and restricted access.

The material excavated from the canal and subsequent dredging formed the basis of an artificial island of approximately 445 acres. It is expected to rise about 10 feet above sea level. The plan is not for tourism: visitors will not be allowed, because the island will not be a park or resort.

It is presented as environmental compensation for the impact of the construction. The proposal is that plants will take root and birds such as grebes and swans will settle there.

An important detail is that the island has already survived winters, including periods with ice deposits, and the fact that it has withstood the test reinforces that the engineering plan is holding up. Poland literally gained new land as a byproduct of the project.

Actual usage so far: more tourism and leisure than cargo.

Despite its official opening in September 2022, commercial use remains very limited. Between January and December 2024, only 31 cargo ships passed through the canal. Fishermen barely used it, with only about 32 vessels during the same period.

The main users were recreational boats: 1466 passages. This fuels criticism that, in its current state, the route functions more as a tourist attraction than as a robust transport corridor. The canal exists, but the logistical promise still depends on the final dredging and ongoing maintenance.

Domestic economic criticism: “Why dig if Gdansk is nearby?”

Another counter-argument points out that Poland already has access to the sea via Gdansk, a major port about 37 miles from Elblag, with a terminal capable of handling the largest ships.

The logic would be to load containers, use a fast highway, and the transport would arrive in Elblag in about an hour.

According to this interpretation, digging a canal costing hundreds of millions of euros would be unnecessary from a practical standpoint.

Former President Andrzej Duda rejected this criticism, emphasizing the symbolic aspect: it’s not about allowing the largest ships to pass, but about opening a route of its own so that Poland doesn’t have to ask permission from a country with which it doesn’t have good relations. In this discourse, the canal represents sovereignty made tangible, not just logistics.

The regional bet: high unemployment and the promise of a “new future”

The project was also touted as an engine for regional growth. The region in question faces unemployment of around 16 percent, while the national average is close to 6 percent. For local residents, the canal represents an opportunity, even if the start seems slow.

Before its opening, the port of Elblag handled approximately 200 tons of cargo per year. Optimistic projections suggest increasing capacity to 22 million tons by 2045, a figure comparable to major ports. It’s a huge promise, used to justify the investment and persistence in the project.

The canal as a complete work: politics, engineering, ecology, and narrative.

Poland didn’t just build a canal. It constructed a national narrative of route independence, faced environmental and economic criticism, and opened a dispute with Russia that mixes military fear, territorial control, and symbolism. At the same time, it created an artificial island as compensation and as a continuous repository for dredged sediments.

The project is a work in progress: open channel, functioning lock, continuous dredging, growing island. and the final part to make access to Elblag truly Useful, yet still being pushed forward. The result is a case where a country literally cuts its own coastline to redefine its regional future and its relationship with the sea.

Do you think Poland is making a smart move by investing so much to avoid dependence on Russia, or does this canal risk becoming an expensive symbol with little practical use?