“Mrs. Martin Luther King,” as she was billed, was the only woman invited to speak that night, taking the stage alongside other prominent antiwar activists. “Have you often wondered,” she began, “why it is that the same President Johnson who speaks so eloquently for civil rights and who has been so moved by the struggle for the right to vote and the anguish of the poor can be so callous about the Vietnamese, and so apparently thoughtless on foreign policy?”

During the prior three months, the number of American troops in Vietnam had more than doubled — to 52,000. The day of the rally, Johnson had authorized US ground forces to engage in combat if requested by the South Vietnamese Army; the US aerial bombardment campaign against North Vietnam made the front pages.

Many in the arena had voted for Johnson just the year before. Now they were openly criticizing his decision to commit the nation to a land war in Asia. Coretta asked the crowd to consider the human cost of that policy.

Casting her eyes to the second tier of Madison Square Garden, ringed with patriotic bunting, she closed with a theme she’d return to in the years ahead: “Ultimately, there can be no peace without justice, and no justice without peace.”

From her days as a student activist at Antioch College in Ohio, where she majored in music and education, Coretta raised her voice against war, racism, and poverty. Her pacifism and support for civil rights led her to join the local chapter of the Progressive Party and attend its national convention in Philadelphia as a student delegate in July 1948.

Speaker Shirley Graham, a playwright, composer, and activist, inspired Coretta, then 21. “What do we want?” Graham demanded of the convention-goers. “That our children may dwell in peace. PEACE without battleships, atomic bombs, and lynch ropes; PEACE without murderers masked as statesmen; PEACE without military conscriptions and mangled, torn bodies lingering on in veterans’ hospitals; PEACE in which to work and build.”

Within the Progressive Party, Paul Robeson most influenced Coretta. After she performed on the same program as the pioneering singer, actor, and activist at a meeting of the party’s Ohio chapter, Robeson urged her to continue her training. Coretta was deeply moved — by his encouragement, but also by the figure he cut onstage, combining song with searing political commentary. “When I began my freedom concerts to raise funds for the movement,” she later wrote, “I patterned my concerts after his performances.”

Her dream of a singing career led her to Boston, where she enrolled at the New England Conservatory of Music in 1951. She arrived in the city with just $15 in her pocket, living on peanut butter, graham crackers, and the occasional piece of fruit until she found work as a domestic helper in the home of an Antioch alum.

In her second semester, a classmate asked if she’d be interested in going on a date with a promising young minister from Atlanta who was earning his PhD at Boston University’s School of Theology. At first, Coretta said no. But her friend gave her phone number to the young man anyway. He introduced himself as M. L. King Jr.

He doesn’t look like much, Coretta recalled thinking when they first met. “But when he talked, he just radiated so much charm he became much better looking.”

On their first date, they talked about peace, war, and racial and economic justice. With each date, she found more to like. He was a good dancer, compassionate, and shared her love of concert music. They spoke deeply about religion, philosophy, and politics.

“In many ways, meeting Coretta Scott opened new worlds for Martin Luther King,” historian Jeanne Theoharis writes in King of the North.

They were married on June 18, 1953, on the lawn of the Scott family home in Marion, Alabama. Coretta wore a pastel-blue dress. Martin’s father, Daddy King, officiated. Coretta told her imposing father-in-law she would not recite the traditional marriage vow to “obey” and “submit” to her husband. “The language made me feel too much like an indentured servant,” she later said.

Coretta Scott King (right) and Juanita and Ralph Abernathy take shelter from the rain at the Poor People’s Campaign march on Washington in 1968.photograph from Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Library

Coretta Scott King (right) and Juanita and Ralph Abernathy take shelter from the rain at the Poor People’s Campaign march on Washington in 1968.photograph from Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University LibraryAs the civil rights movement gained momentum, Coretta’s national profile grew as well.

In 1957, she helped launch the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy to raise awareness about the dangers of nuclear testing. She performed in fund-raising concerts and often stood in for Martin at public events.

She was among 50 American women affiliated with Women Strike for Peace who attended the United Nations disarmament conference in Geneva, in April 1962. Weeks later, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover received a field report, “Coretta Scott King, aka Mrs. Martin Luther King, Jr. INFORMATION CONCERNING (SUBVERSIVE CONTROL).” The House Un-American Activities Committee had requested passport files on all the women who had traveled to Geneva. Coretta’s photo and her parents’ names were forwarded to the FBI field offices in Atlanta and New York. The report is a chilling reminder of the official surveillance Coretta, like Martin, endured.

Coretta had spoken out against the Vietnam War earlier and more forcefully than Martin, and he consistently praised her activism. When the television interviewer Arnold Michaelis arrived at the King family home in Atlanta in late 1965, Martin was in the middle of a whirlwind year.

Noting Coretta’s growing visibility in the peace movement, including her speech at a major rally in Washington, D.C., just days earlier, Michaelis asked, “Did you educate your wife on activism?”

“Well, it may have been the other way around,” Martin replied. “I think at many points she educated me.” He recounted the early years of their relationship, Coretta’s deep commitment to racial and economic justice—and to pacificism. “I wish I could say to satisfy my masculine ego that I led her down this path,” Martin said, “but I must say we went down together, because she was as actively involved when we met as she is now.”

From summer 1965 until his death, the timing and tone of Martin’s public statements on Vietnam bore the imprint of Coretta’s influence.

Coretta’s critique of the Vietnam War was multifaceted. She argued that it siphoned vital resources from domestic needs, turning attention and funding away from programs that could improve the lives of Americans. She emphasized the legacy of Colonialism and the importance of fighting for independence.

On the same map that triggered fears of communism, she saw dozens of newly sovereign nations in Asia and Africa struggling to define themselves in the shadow of global superpowers. She acknowledged the complexity of the geopolitical moment — but believed it could be explained in ways that resonated with everyday Americans.

On April 4, 1968, Martin was assassinated. Three weeks later, Coretta stood before 80,000 people in New York’s Central Park, vowing to carry on the work of peace “until the last gun is silent.”

“UNTIL THE LAST GUN IS SILENT” will be published on Tuesday.

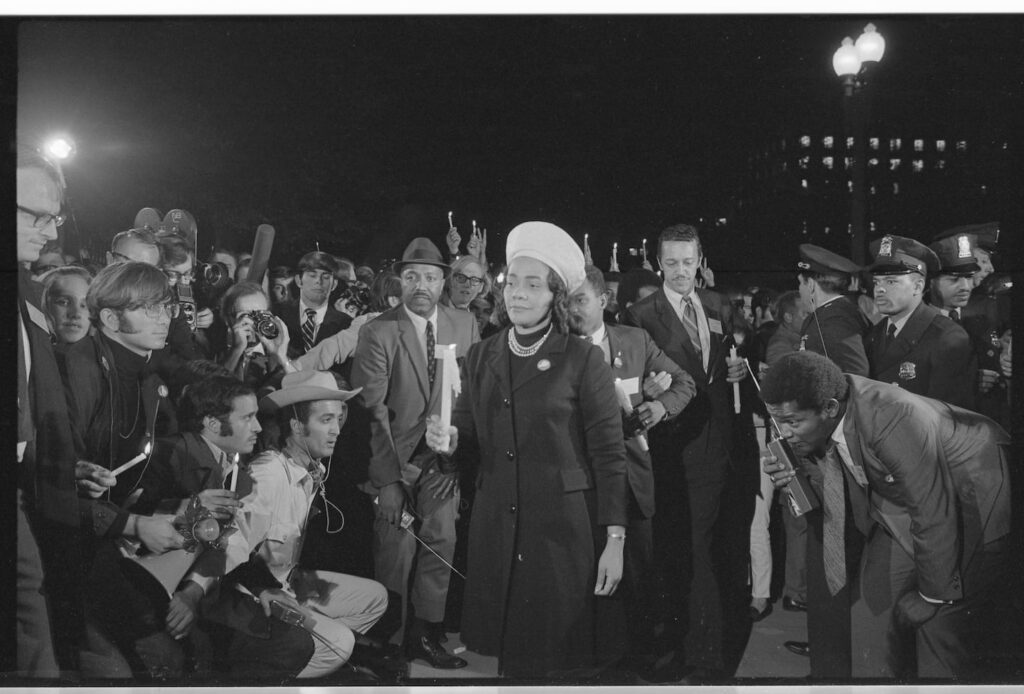

“UNTIL THE LAST GUN IS SILENT” will be published on Tuesday.In October 1969, she led nearly 35,000 people in a candlelight march to the White House as part of the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam. The next month, half a million people rallied in Washington, D.C., for the second moratorium protest, the climax of three days of antiwar actions in the capital and across the country. New York Senator Charles Goodell, the most prominent antiwar voice in the GOP, joined Coretta as she marched to the Washington Monument.

She had become the most visible leader of the two largest protest days in American history, giving countless ordinary citizens the courage to confront their own government. The ensuing wave of solidarity had real impact: Despite their differences, both President Johnson and President Nixon paid close attention to public sentiment around Vietnam. Each weighed decisions about troop commitments, bombing campaigns, and peace negotiations against the size and visibility of organized opposition.

Throughout these protests, Coretta advocated for a vision of patriotism where love for one’s country is strengthened — not diminished — by dissent. “We love America,” Coretta told a group of college students in 1965. “Our job is to save the soul of America.”

This excerpt was adapted from UNTIL THE LAST GUN IS SILENT by Matthew F. Delmont, a professor of history at Dartmouth. Published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2026 by Matthew F. Delmont. Send comments to magazine@globe.com.