The landscape of Bosnia and Herzegovina still bears the marks of its violent dissolution. This photo essay traces how the legacy of conflict continues to shape everyday life.

The history of this shattered country is still linked to its dissolution. The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia slowly crumbled with Josip Tito’s death, eventually breaking apart in a series of armed conflicts of which the Bosnian War between 1992 and 1995 was by far the most complex and bloody.

The causes of this war can be sought in the prevailing nationalist ideologies that fueled independence movements, heightened by economic and cultural differences, culminating in head-on clashes among the country’s Serbian, Bosniak, and Croatian communities.

In July 1995, the small town of Srebrenica, designated a “protected area” under the protection of a Dutch contingent of the European Union Protection Force, was the scene of the genocide of over 8,000 Bosniak men and boys by the Bosnian Serb army under the command of Ratko Mladic, known as the “Butcher of Bosnia.”

The Dayton Peace Agreement, signed in the U.S. state of Ohio in November 1995, brought an end to the Bosnian War. Serbia’s Slobodan Milosevic, Croatia’s Franjo Tudjman, and Bosnia’s Alija Izetbegovic signed these accords under strong diplomatic pressure from the U.S. administration led by Bill Clinton.

Today, Bosnia is divided into two main entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska, to which is added the small autonomous district of Brcko. It has a tripartite government, described as the most complex institutional system in the world, based on an intricate architecture of parliaments, governments, and presidencies, designed 30 years ago to represent the country’s three main ethnic groups following the war. Now, it is considered responsible for chronic stagnation.

The younger generations are struggling to break away from a narrative closely linked to the events of the conflict, while rural areas are experiencing social and educational poverty that offers no prospects for the future. The country is extremely fragmented, with ethnic and religious divisions still tracing themselves across the territory.

Countryside between Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Tuzla, the country’s third-largest city.

A house riddled with bullet holes along one of the main roads leading to the center of Tuzla. During the Bosnian War, Tuzla remained under the control of the Bosnian armed forces, but was the scene of a tragic massacre and endured heavy shelling by Serb forces.

Brcko District. Fishermen on the banks of the Sava River, which separates Bosnia from Croatia. The river is crucial for Brcko as it is home to Bosnia’s largest river port and currently offers numerous opportunities for recreational and tourist activities.

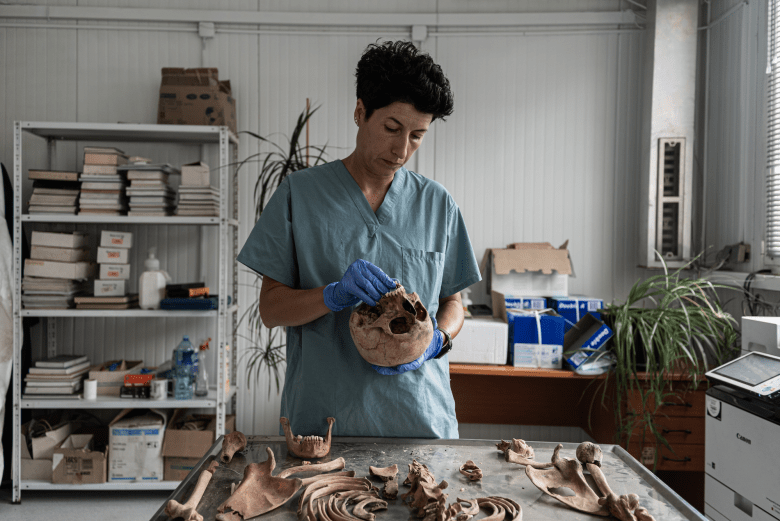

The remains of a victim of the Srebrenica massacre awaiting reassembly, classification, and identification on a morgue table in the forensic anthropology laboratory in Tuzla. Many Serbs both in Bosnia and Serbia continue to deny that the mass killings in Srebrenica constituted genocide.

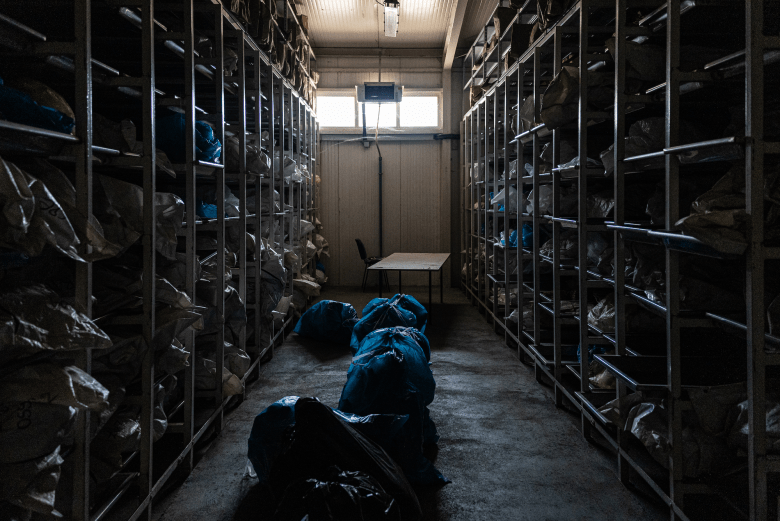

There are still many unidentified victims, reduced to a few remains collected in white bags, placed on the shelves of a morgue where doctors and forensic anthropologists from the International Commission on Missing Persons work.

Dragana Vucetic, forensic anthropologist with the International Commission on Missing Persons, working to reconstruct the skeleton of one of the victims of the Srebrenica genocide.

Thousands of participants took part in the 2025 edition of the Mars Mira (Peace March), a walk on the anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide to commemorate the victims and call for speedier prosecution of those responsible.

Children watch the start of the Mars Mira just outside the village of Nezuk.

A small cemetery along the Mars Mira route near Kamenica. One of the largest wartime mass graves in the entire country was found here.

A group of Bosnian soldiers poses for a photo along the route of the Peace March. Soldiers set up tent camps, cook meals, and provide medical support for marchers.

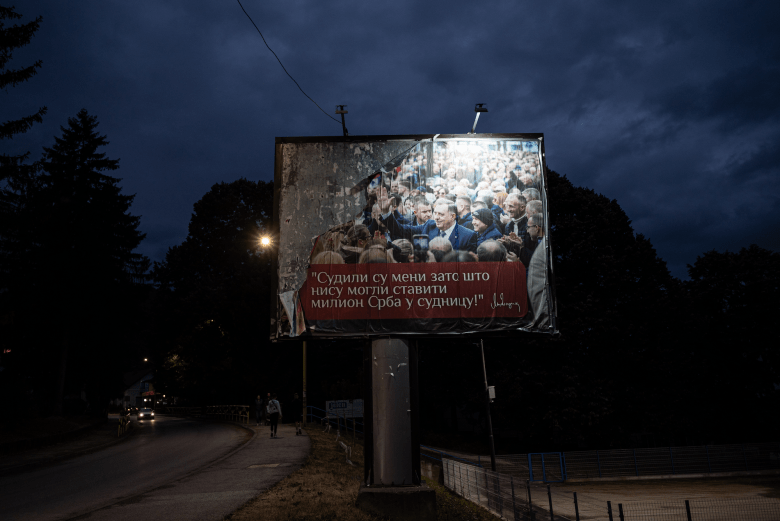

A sign supporting the former Republika Srpska leader Milorad Dodik in the small town of Vlasenica. The Cyrillic text reads: “They prosecuted me because they couldn’t bring a million Serbs to court.”

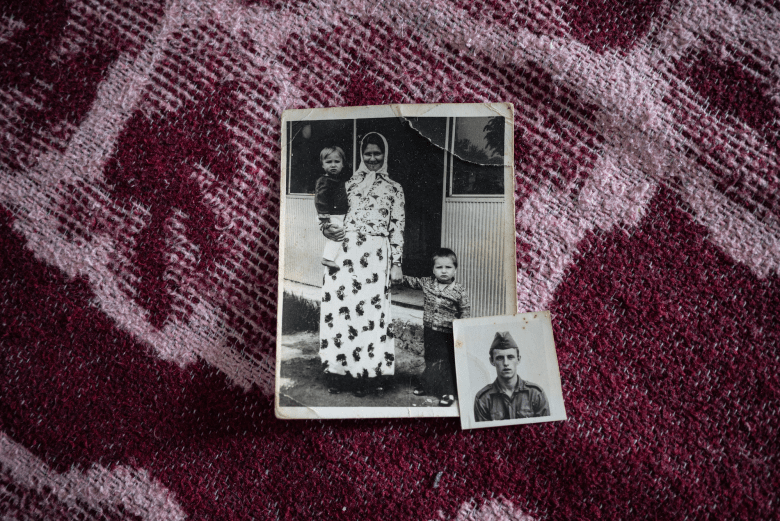

Omerovic family photos: Alisa with her toddler son Sadik and three-year-old Mensur. A cousin is seen in the small passport photo.

Mensur Omerovic stands in front of his house in the village of Sikiric on the Drina River. His childhood home, to the right of the not-yet completed house, was burned down by Serbs in 1995.

A young woman met during a walk along the Drina poses for a photo.

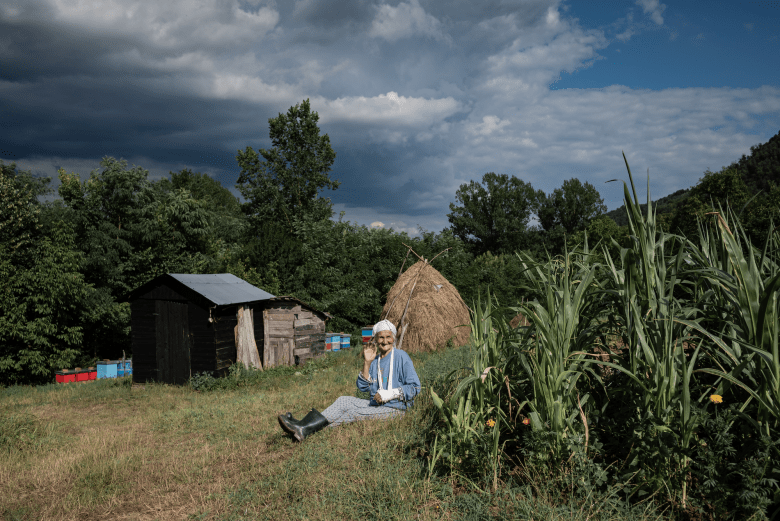

The mother of a friend of Mensur Omerovic rests in a field near her home in Sikiric.

A child draped in the Bosnian flag looks at gravestones in the Srebrenica memorial cemetery in Potocari on 11 July, the official day of mourning for the victims.

A girl grieves during the burial of a relative, one of seven Srebrenica victims whose intact remains were finally laid to rest in the Potocari cemetery on 11 July.

Women praying during the commemorations of the 30th anniversary of Srebrenica.

A moment during the burial of one of the seven bodies that were laid to rest in the Potocari cemetery on 11 July.

Many houses along the 11-kilometer road from Potocari to the Serbian military cemetery in Bratunac display photos of Serbian soldiers and civilians who died in the Bosnian War and previous conflicts. For years Bratunac has held a memorial ceremony on 12 July, one day after the much larger commemorations for the victims of Srebrenica.

The “Mothers of Srebrenica” association gathers women who lost loved ones during the July 1995 mass killings, and who, ever since, have sought justice for those responsible and the proper burial of the many victims whose bodies lie in mass graves.

Markale is Sarajevo’s covered market. It is a symbol of the city and its long siege during the war. More than 100 people died and hundreds more were injured here when the market was hit by mortar shells in February 1994 and again in August 1995.

Kino Bosna is one of the most popular entertainment venues in Sarajevo. It hosts live music evenings featuring traditional Balkan folk music.

Nermine, Dodji (Nermin, Come), a statue near the Great Park in Sarajevo, captures one of the most tragic episodes of the war, when Bosnian Serb soldiers ordered Ramo Osmanovic, a Bosniak man, to call on his son and others in hiding to surrender. Nermin joined his father, and both were subsequently executed. Their bodies were found and identified in a mass grave in 2008.

Benjamin and Adna from the street art collective Obojena Klapa pose for a portrait outside their Manifesto Gallery, a small space in Sarajevo for cultural events and exhibitions of artists from all over the former Yugoslavia. On the left is Daniela, a painter from Banja Luka, the second largest city in Bosnia and Herzegovina and administrative center of Republika Srpska.

A view of Sarajevo at sunset from the Yellow Bastion, which was part of the old town’s defensive wall.

On 9 November 1993 the Stari Most, the Old Bridge of Mostar, collapsed under Bosnian Croat artillery fire. A jewel of Ottoman architecture, its destruction was the culmination of the war waged by the Croats against their neighbors and recent allies the Bosniaks. Strategically unimportant, it was targeted as a symbolic attack on memory, and shared cultural heritage. The bridge was rebuilt in 2004 with a total investment of 12 million euros.

One of the Stari Most divers. Young men dive from the bridge into the icy waters of the Neretva in an old tradition, revived as a symbol of the city’s rebirth and the resilience of the Bosnian people, and to attract tourists who flock to the riverbanks and the bridge in search of the perfect shot.

Federico Tisa is a documentary photographer from Turin. He works on medium- and long-term projects using photography as part of an anthropological narrative.